Five Steps to Better Mycoplasma Hyopneumoniae Control

GLOBAL - Pig health is critical for maintaining animal welfare and ensuring a steady supply of safe and affordable pork. “Sustainable Health“ is a series of articles about common health issues in today’s swine herds and options available for managing them sustainably, writes Lucina Galina, DVM, PhD.For pig producers and veterinarians, the health and economic impact of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (MH) is clear. In the US, enzootic pneumonia caused by MH is considered one of the “big three” respiratory diseases in swine, following porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome (PRRS) and influenza.

Economic losses due to reduced growth, poor feed efficiency and extended time to market can significantly hurt the producer’s bottom line. Recent estimates indicate that the cost of uncomplicated MH infections in large production systems is more than $1.00 per pig and $10 in MH-positive sites co-infected with influenza and PRRS virus.

Often less clear, however, is how to manage this costly and persistent pathogen. Overall, disease control has improved in recent years, thanks to the production of MH- and PRRSv-negative breeding stock, the adoption of segregated systems — in which pigs of a similar age are raised and moved together — and the development of strategic treatment and vaccination protocols.

The challenge is that differences in the MH health status of incoming breeding stock and sows at the recipient farm can have a negative impact on health — with costly consequences.

MH-control challenges

For example, when MH-negative gilts are introduced in MH-positive systems without proper acclimation, subclinical or clinical disease can develop, increasing vertical transmission from dam to piglet. Higher rates of vertical transmission mean more pigs colonized at weaning, which is the greatest predictor of clinical disease in the finishing herd.

We have also learned that pigs that have been exposed to MH can continue shedding for up to 250 days. Controlling shedding in a population is the most challenging aspect of disease control since there are currently no reliable methods of ensuring uniform exposure of all animals in a population. Additionally, facilities that allow for a long enough “cool-down” period to discontinue shedding are rarely available.

Vaccination, medication and proper all-in, all-out movement of pigs are therefore necessary but insufficient for preventing colonization. Successful MH control must begin with acclimating gilts, as part of a comprehensive plan that includes multiple strategies.

Five steps

To help veterinarians and producers get a better handle on MH control, my Zoetis colleagues and I teamed up with eight experts from animal health, academia, diagnostics, swine veterinary practice and a breeding-stock company to review the latest knowledge and best practices for managing MH.

The outcome is a 60-page manual, titled “A Contemporary Review of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Control Strategies,” which outlines a systematic, five-step approach for managing MH in today’s segregated production systems:

1. Establish current herd status of MH on the farm and set appropriate goals.

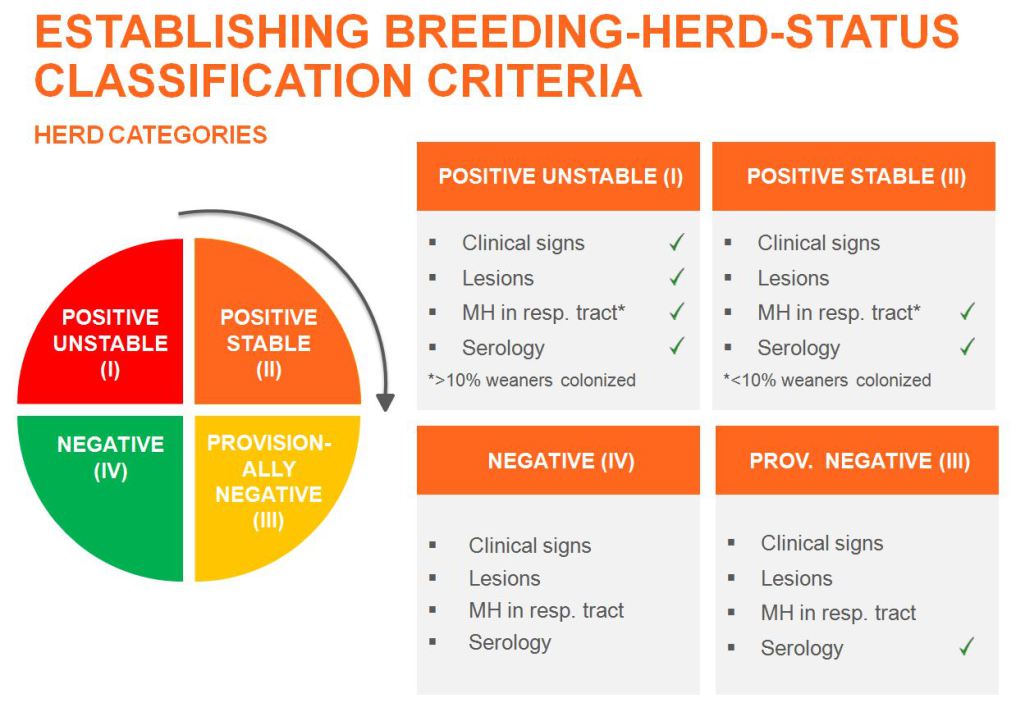

A breeding-herd classification allows veterinarians to determine a baseline and set appropriate goals. For example, a positive, unstable herd is likely to require a more aggressive control strategy than a positive, stable herd. The use of a common classification language should also improve communication between stakeholders, including veterinarians, producers, diagnosticians and breeding-stock companies. A summary of the four MH categories for breeding herds is shown in Figure 1.

Most swine herds fall within one of the herd categories outlined in the table above, but their responses to challenges may not always be black and white. The most critical guideline is the percentage of pigs colonized at weaning. This criterion clearly differentiates positive, unstable herds from positive, stable ones.

2. Leverage diagnostic techniques that reveal your current status.

The appropriate diagnostic approach for your farm will depend on which question needs to be answered. The question could be whether MH is present in the population, or whether MH is causing disease. These are two different questions that call for different diagnostic approaches.

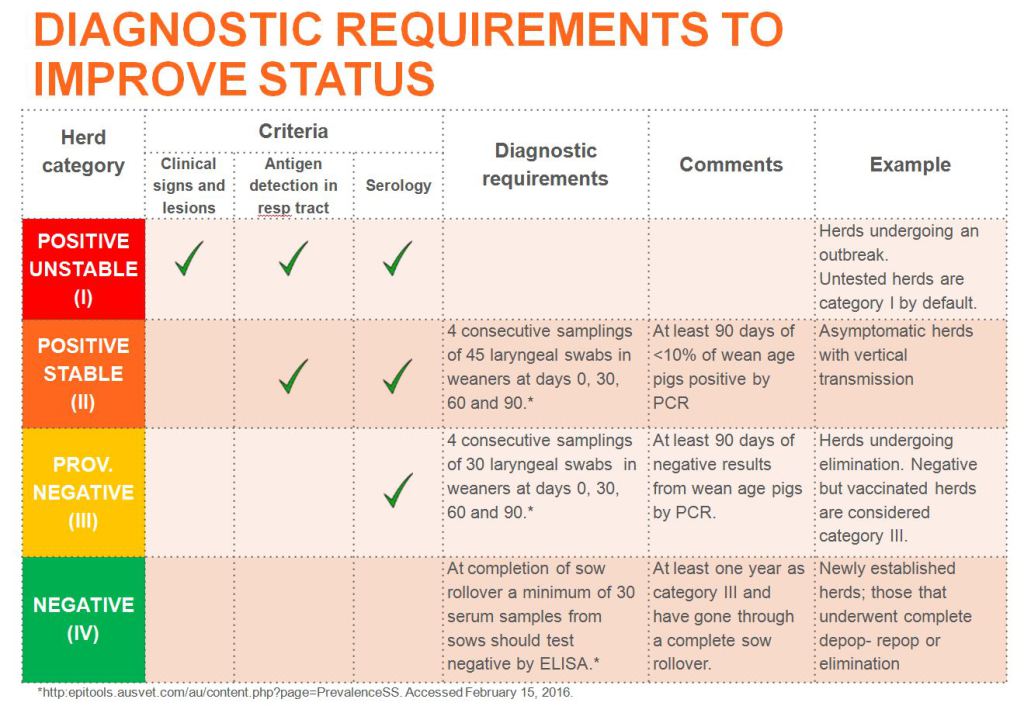

Detailed diagnostic requirements for health-status categories, shown in Figure 2, take into account the expected prevalence of MH in the population, as well as the sensitivity of the sampling technique and diagnostic tests. Testing should be repeated, regardless of which diagnostic method is used.

3. Understand and manage risk factors that influence disease transmission at all stages of production.

Many factors influence MH transmission. Some important risk factors include location of infected facilities within a 9 km (5.6 mi) radius, lack of isolation and acclimation facilities, lack of gilt exposure programs, introduction of replacement breeding stock with different health status, insufficient time for gilts to discontinue shedding, high proportion of at-risk females, poor lactation management, poor pig management and lack of vaccination.

Adequate biosecurity is critical to mitigate or eliminate these risk factors. Some biosecurity risks include transmission via fomites, equipment and transport; lack of cleaning, disinfection and drying of facilities; lack of all-in, all-out movement in the farrowing room; and the presence of concurrent diseases.

Understanding risk factors helps determine the most realistic and sustainable control strategy. For example, trying to achieve a negative status using disease elimination may not be suitable in an unstable herd that has a high risk of re-infection due to its location. Disease control could be achieved by moving to a healthier status such as stable herd.

4. Consider control measures, including maintaining a negative herd, vaccination, medication and disease elimination.

If your herd is negative, the best strategy is to keep it that way. If your herd is positive, control can be achieved by minimizing disease with vaccination or medication or by eliminating MH. Vaccination and medication alone — without being part of a disease-elimination strategy — can be expected to reduce clinical signs, shedding and economic losses but not to eliminate the organism from the population. Vaccination of weaned pigs is unlikely to result in full disease control in finishers if the sow farm is unstable.

Medication can be used for control, treatment or disease elimination. For successful disease elimination, gilts should be acclimated to stabilize the sow herd. Then, the breeding herd will go through exposure and recovery phases, during which all pigs must be exposed to MH and be confirmed positive before strategic medication, disinfection and vaccination.

All these steps should be carried out with proper timing and orchestration. The goal is to eliminate MH shedding from mother to piglet and reduce the number of positive piglets at weaning.

5. Monitor the efficacy of interventions.

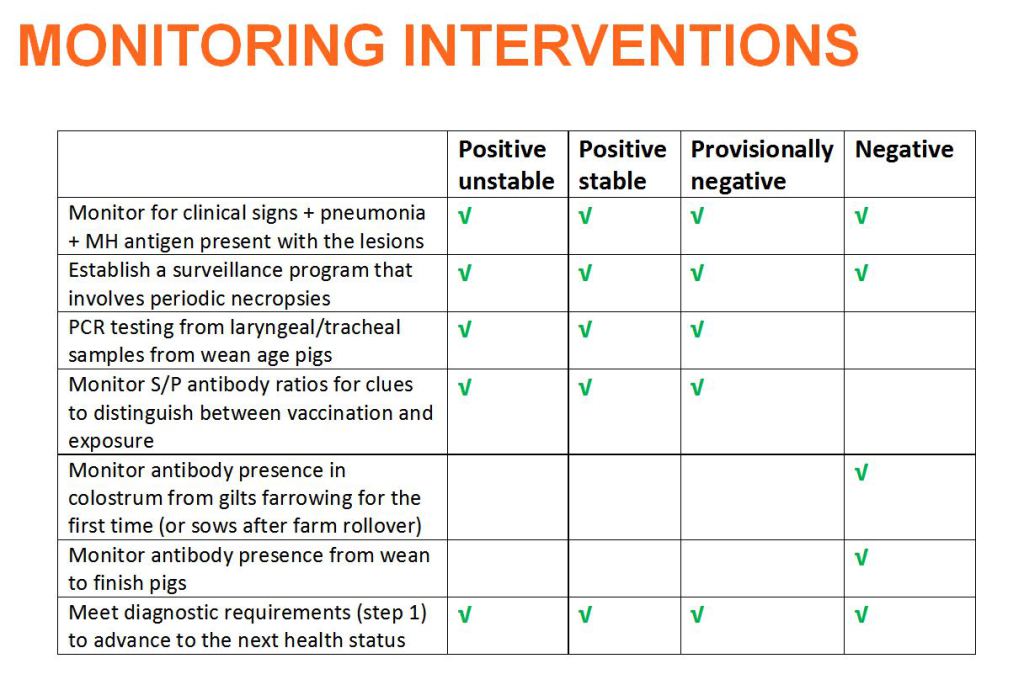

Control interventions should be monitored every 6 to 12 months to determine if the herd status has been maintained (Figure 3). There are multiple sampling procedures and diagnostic tests for monitoring MH infection, colonization and disease progress.

Choice of procedure depends on several factors, including infection, clinical signs, disease prevalence, pig age, sampling technique, diagnostic test sensitivity and time to develop antibody response. Most important is to be certain of the current status of the population; the herd must meet the diagnostic criteria shown in Figure 2 to properly determine the correct classification.

For a free download of “A Contemporary Review of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Control Strategies,” click here.

Taken from Voice of Sustainable Pork.