Fit for transport: how are travel conditions impacting the state of sows at slaughter?

The responsibility for the state of a pig when it reaches slaughter is shared by both the farmer and the driver, but could transportation conditions be having a bigger impact on pig health than current legislation acknowledges?If a pig is deemed fit for transport on farm but unfit when it is assessed by the vet at the slaughter facility, who is responsible for accepting the penalties for the transportation of unfit animals laid out in EU legislation? Currently, farmers and drivers take the brunt of the blame in this scenario but this hardly seems fair, especially on producers who have worked hard to ensure the good health and welfare of their animals in the months (sometimes years) leading up to the time for slaughter. It also raises the question: is penalising farmers for the state of pigs post-transportation actually addressing the real issue, which may be the conditions under which livestock are transported?

An ongoing project conducted by researchers from Aarhus University has begun to address this topic with the aim of determining whether, if quantified, the clinical condition of sows change between observation on farm, pre-transport and at post-transportation assessment. We spoke to Dr Mette Herskin, one such researcher, who discusses the major issues encountered when transporting sows and the fact-finding mission of her latest project.

What are the major health concerns when transporting sows and how do these concerns differ to transporting other categories of pigs?

Sows are different from the other categories of pigs. In pig transport, we predominantly work with young pigs between 25 to 30kg that are being transported for fattening; market-weight pigs (around 110kg) going to slaughter; sows; and boars.

Sows are different because they are in the final part of their production cycle, which they have been in for a number of parities – in Denmark the mean number of parities of cull sows is around five to six. They are not weak but they carry the load of having been in the production system for a long time so they’re not young and healthy like the market weight pigs being transported to slaughter.

On top of that, sows are often transported at a particular time due to feed economics and lack of space in farrowing and gestation units, so many are transported very soon after they have weaned the last litter – sometimes the same day as weaning. Now if you look at the lactation curve for sows, their milk production is peaking around weaning and it takes some time post-weaning for milk production to slow down and eventually stop. This means that they have a very high metabolism which makes them particularly sensitive to heat stress.

Another challenge is that when mature females meet and mix, they will fight. Sows are big so when they fight inside a truck or confined facility, they can cause each other some real damage. Weaned pigs fight but it is unlikely that they will really injure each other like sows do.

© Aarhus University

At what temperature does it become dangerous to transport sows?

A recent American study showed that sows have a higher dead-on-arrival percentage compared to other categories of pigs, and that this rate increases in the summer months.

Sows are more prone to heat stress than the other categories of pig due to the fact that they carry more weight and their surface area to body mass ratio is lower so they struggle to cool down.

We saw in our study, based in Denmark where the climate is very temperate, signs of dehydration in our sows starting as early as 15 degrees Celsius. We don’t know for definite what this cut-off temperature should be, this is something we’re continuing to investigate, but the signs of deterioration in sow condition did start at temperatures below current legal standards for transportation. In Europe it is legal to transport sows up to 30 degrees Celsius but they will probably experience heat stress at lower temperatures than this.

I think in this situation, it’s important to consider the recommended environmental conditions for sows on farm to ensure good health of the animal. Now consider that in the transport vehicle there is a higher stocking density, there is no access to water and sows are being mixed with unfamiliar sows so they are likely to fight. All of these factors increase the temperature inside the truck at a time when it is already difficult for sows to regulate their body temperature.

These factors considered, the temperature limits that suit sows during transport will most probably be lower than on farm.

What was the primary aim for your latest study?

To comply with European legislation the fitness of the sow should, in principle, be determined on farm before transportation, and then post-transport this sow is assessed again by a vet who will determine whether she is still fit.

Thus farmers or drivers can be fined or receive penalties if the condition of the sow is unacceptable when they reach their destination. There may be dispute about what the sow looked like on the farm and her condition after transport.

Our study aimed to answer the question: will the clinical condition of sows change (if quantified) between observation on farm, pre-transport and post-transportation assessment.

Fitness for transport is a complicated issue so this study was not designed to solve any problems directly. It was an exploratory study, designed to examine a welfare issue characteristic of this part of pig production.

© Aarhus University

How was the study conducted?

We took observations from 522 sows - from a number of different farms - distributed over 47 journeys.

We gathered observations from each producer about each sow, including weaning date, the time of their last feed, their parity number, and other valuable production data.

A veterinarian also formulated a full clinical examination for us, using more than 30 different clinical observations per sow, including:

- general condition;

- body temperature;

- skin colour;

- wounds/lesions;

- vulva lesions;

- respiratory rate;

- skin elasticity as proxy for hydration; and

- the incidence of torn hooves and hoof length.

Some of these observations could change during transport and some could not, for example, hoof length should not change between the first examination on farm and the second at the slaughter facility, but skin elasticity, or skin lesions, could change.

We also wanted to characterise what cull sows actually look like while still on farm as there is no real profile for them in scientific literature.

Sows in the study were transported under conditions as stipulated by Danish and EU legislation: transport times varied but did not exceed the national eight-hour limit; commercial stocking density was applied.

For biosecurity reasons, we could only visit one farm in a day so we took our observations at one farm of the multiple units per day that the driver would visit on the way to the slaughter facility.

Transport times

In Denmark the law dictates that transport times for cull animals cannot exceed eight hours so our study, as it was based in Denmark and nationally funded, investigated transportation of eight hours or less. The pigs in our study were also transported directly from the farm to slaughter, but detours via assembly barns and auctions may be another challenge for welfare.

Obviously, legal transport times vary greatly in different countries and regions, but what seems to be happening globally is that fewer slaughterhouses are accepting cull sows so there is now a global trend for increasing transport times, particularly when moving sows.

© Aarhus University

What were your observations from the investigation?

We found that a significant proportion of the sows deteriorated in condition between the farm and arrival at slaughter. For many of the variables that we were investigating there was a deterioration or decline.

- Superficial skin lesions increased.

- Wounds increased.

- Skin elasticity decreased/got worse.

- There was evidence of dehydration.

- Gait score worsened.

- More vulva lesions were noted.

- An increase in torn off hooves was observed.

How do we manage this better?

Together with Danish Crown, the Danish Meat Research Institute, the Danish pig industry, and driving company, SPF, we now run some intervention trials. These trials are still conducted under commercial conditions to produce realistic data, but we can implement some realistic treatments or changes to the way we currently transport pigs, and indeed all livestock.

From this we can compare different experimental treatments, such as transport duration. Duration is something that from a political point of view, is always picked at, but we don’t often know how important the duration of the actual journey is for the sows. We still transport under eight hours only as this is the legal limit in this country (Denmark).

We’re also looking at how the driving safety rules, whereby drivers must stop for a 45-minute break every 4.5 hours, impact animals being transported. There’s a lot of speculation that these stationary periods are bad for the sows as we know the temperature rises when there is no flow of air through the truck. We also know that there are a lot of risk factors for fighting between sows, a potential drop in air quality and heat stress being a couple of those, and both of those factors would worsen when the vehicle is left stationary for any extended period.

We’re examining this in more detail now, monitoring sow health after a journey with a 45-minute break and without a break where two drivers take shifts.

Another treatment we will be looking at is the use of partitions in a commercial truck. We’re hypothesising that a lot of this deterioration is related to the fighting and not to just being on a truck. We would like to be able to separate the effects of just being on a truck from the effect of mixing.

I know that this sounds, and may be, highly unpractical but this is a method of determining the true causes of deterioration in sow health during transportation which is something we need to know in order to come up with viable solutions.

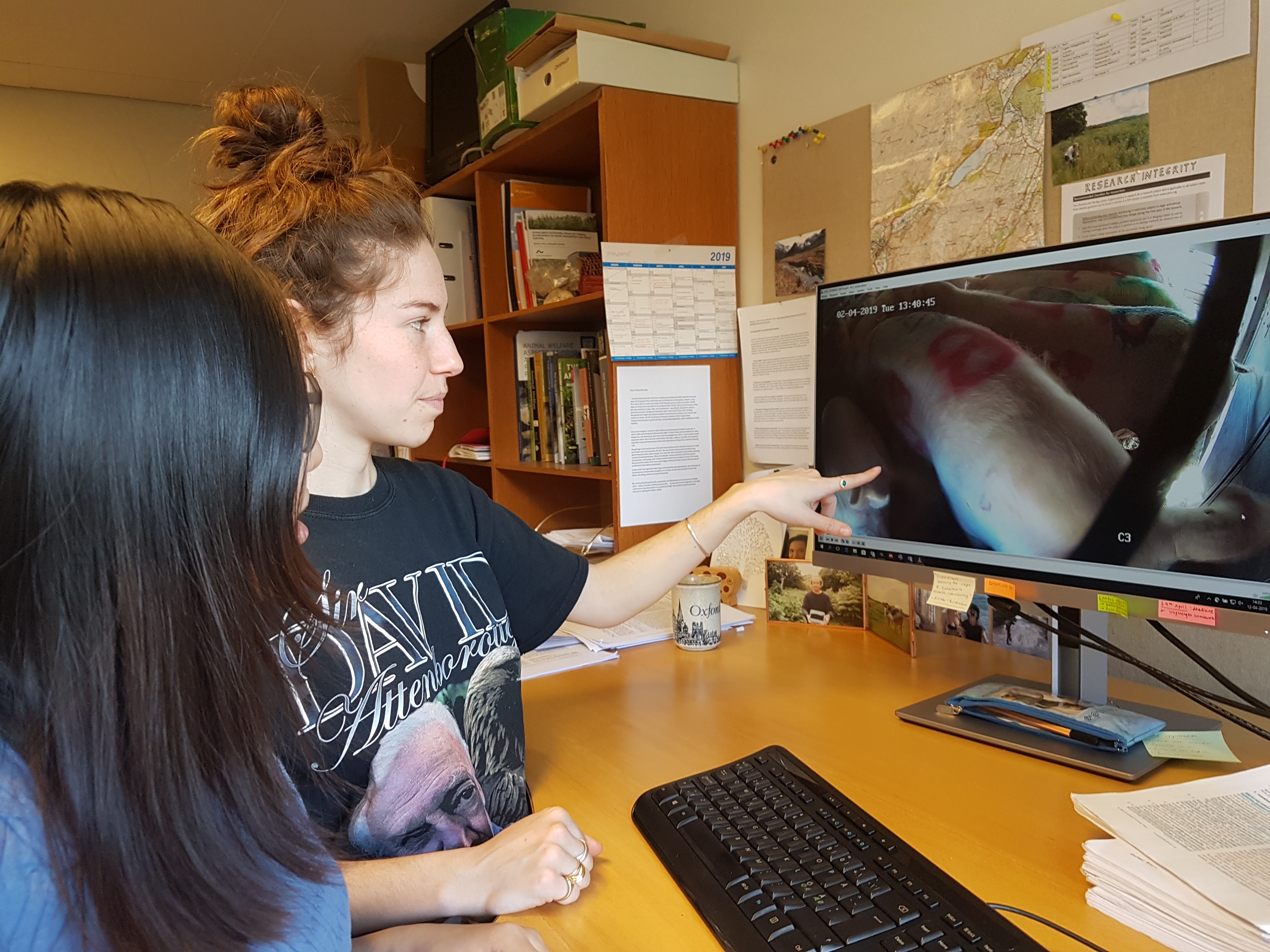

We’re also planning to run a trial to compare journeys with and without access to water. We will investigate a lot of the same health factors before and after the journey, we will record climatic conditions inside the truck throughout the duration of the journey (temperature, humidity and G-force loggers), and we have video cameras to record the behaviour of the sows during transport.

Videoing during transport has never been done before and this is a challenge, due to the inquisitive nature of the pigs and their capacity to damage equipment, and due to the space constraints in the truck making it very difficult to get a clear view of each pig.

© Aarhus University

How can new technology aid with managing the environment that sows are transported in?

I think there is great potential for technology but from my side, this has not been exploited.

There are companies who have started implementing technology which allows continuous monitoring. They develop different loggers for monitoring the condition of the animals both during transport and after transport. There seems to be large potential for technology like this.

Sensors and loggers could allow us to tackle the issue of heat stress directly. Warnings and alarms can alert the driver to tell him the temperature is getting too high in the truck so that he knows he must turn on the mechanical ventilation or the water misters/sprinklers. As the climate changes globally, there will be more of a focus on heat stress in transported animals so sprinklers may not be common on trucks now but will be in the future.

This summer we’ve heard from all over Europe that farmers have had to keep animals on farm and delay transportation because it has been too hot to transport them – which is a burden on the industry. If we work on transportation solutions that remove temperature as a deciding factor, then that burden is reduced.

In our investigations and communication, we have used the term deterioration because the condition of the sows clinically gets worse between loading and exiting transportation to slaughter. We are not saying that this is necessarily a huge problem but it certainly raises the question: can we develop systems to avoid this?

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fogsgaard, K.K., Herskin, M.S. and Thodberg, K. | ||||

| (2018) | Transportation of cull sows-a descriptive study of the clinical condition of cull sows before transportation to slaughter.. Translational Animal Science | 2(3):280-289 | ||

| Herskin, M., Fogsgaard, K., Erichsen, D., Bonnichsen, M., Gaillard, C. and Thodberg, K. | ||||

| (2017) | Housing of cull sows in the hours before transport to the abattoir—An initial description of sow behaviour while waiting in a transfer vehicle.. Animals | 7(1):1 | ||

| Thodberg, K., Fogsgaard, K.K. and Herskin, M.S. | ||||

| (2019) | Transportation of Cull Sows—Deterioration of Clinical Condition From Departure and Until Arrival at the Slaughter Plant.. Frontiers in Veterinary Science | 6 |