UK farm assurance falls short on ambition to provide “a life worth living” for sows

Why are citizens concerned if British legislation on farm animal welfare is considered world class? And do assurance schemes guarantee that animal welfare principles are implemented on farms?FAI’s veterinary consultant Laura Higham recently presented at the 12th Boehringer Ingelheim Expert Forum on Farm Animal Well-being in Prague, and made the case for phasing out all confinement systems in pig production to enable species-specific behavioural opportunities as a necessity, not a luxury.

The term “consumer” is a very familiar word in food business. It describes shoppers as people with similar behaviours and drivers in their selection of supermarket produce; primarily interested in product consistency and price points.

But things are changing – through a growing contingent of conscientious consumers who are wishing to create a more positive society by utilising their spending power to drive ethical food supply chains. As citizens, we don’t just want choice, we want roles in the reinvention and reshaping of our food system, and we are increasingly interested in the animal welfare standards behind the meat, milk and egg products that we buy.

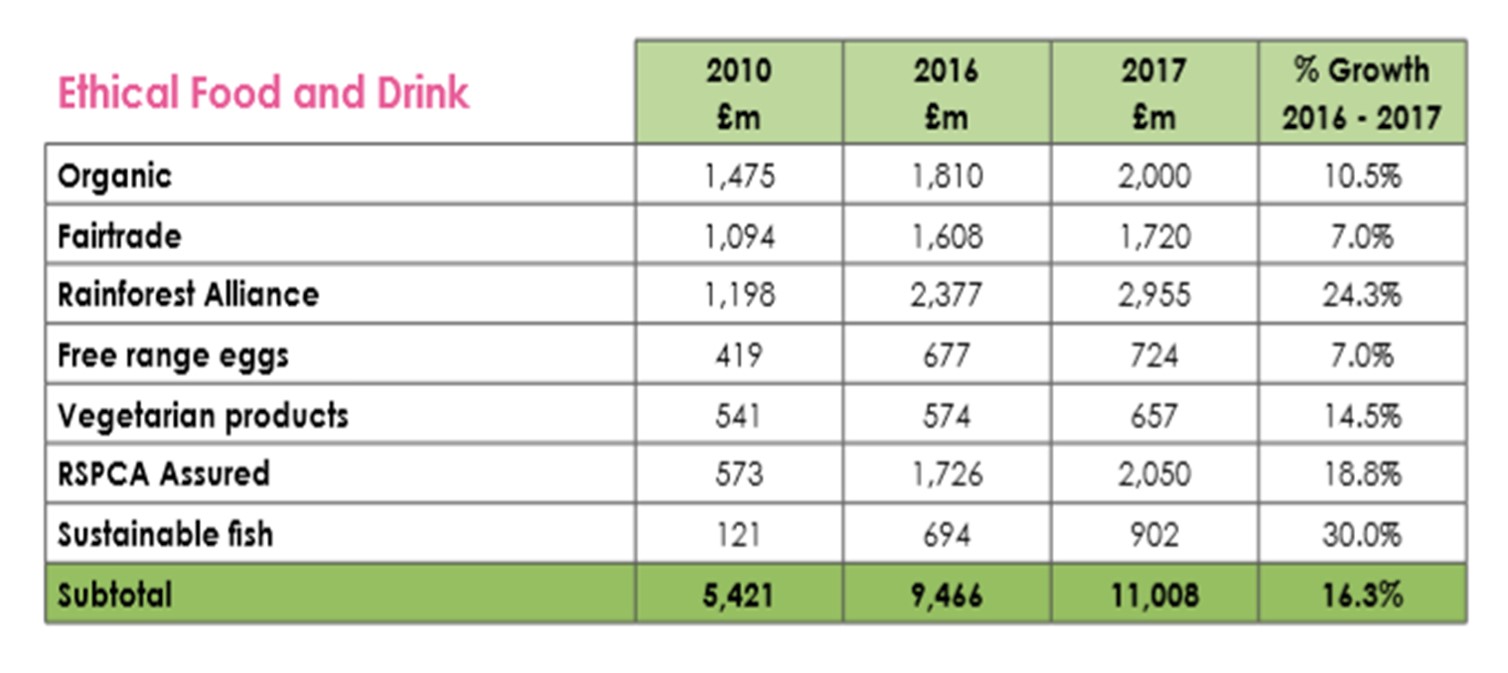

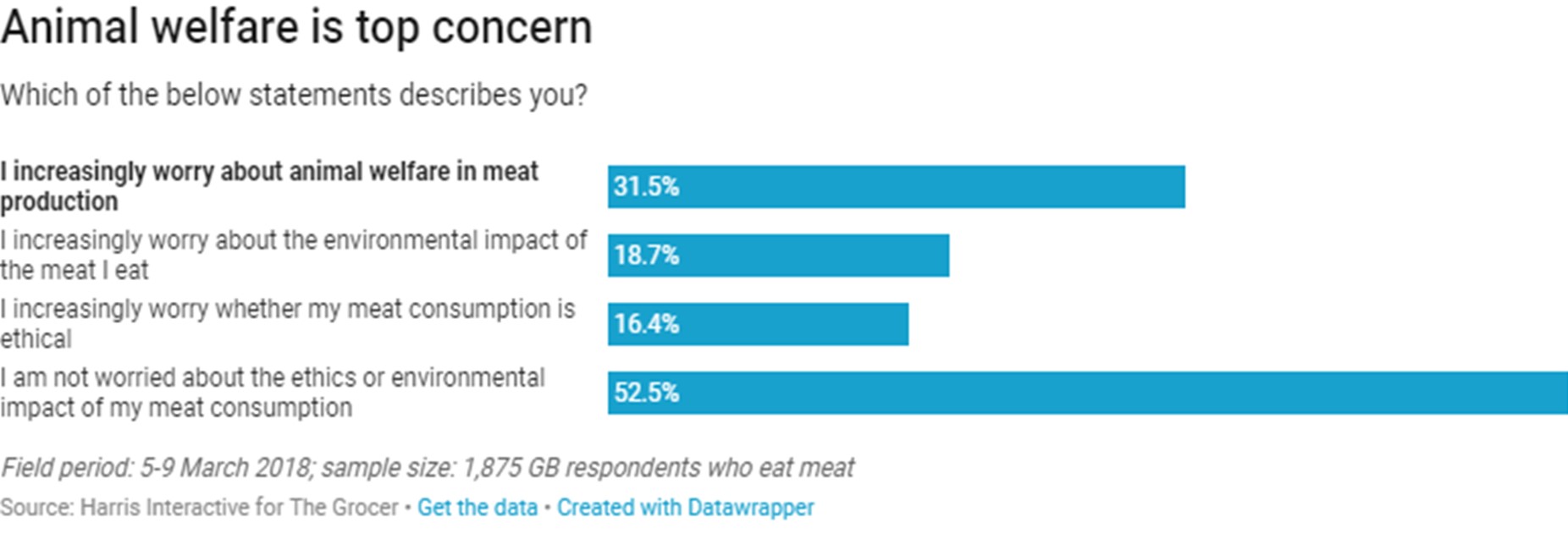

Animal welfare is an increasingly important factor in purchasing decisions by citizens globally. According to surveys, around 70 percent of respondents in the UK, USA and Australia are concerned about farm animal welfare. We can see from results of surveys by the Ethical Consumer and The Grocer that there is robust growth in ethical markets and that animal welfare is the top concern amongst many UK shoppers (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Another survey suggested that 72 percent of respondents in China considered farm animal welfare important, with 75 percent willing to pay more for higher welfare pork. This ‘citizen shift’ is translating in to purchasing decisions, evidenced by the cage-free egg movement seen in many countries across the world, and an increase in the trend for less-but-better flexitarian diets.

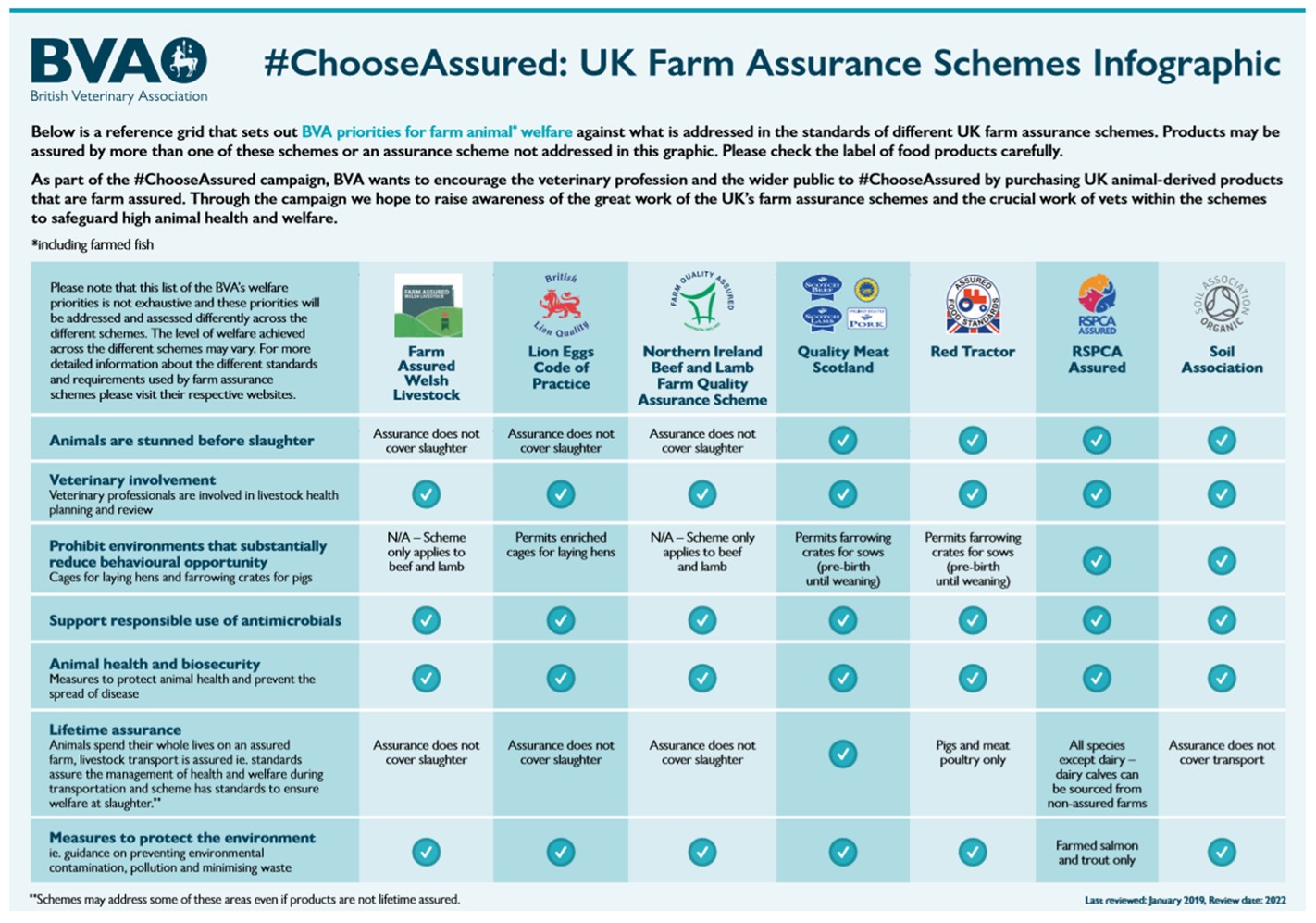

Veterinary surgeons are key stakeholders in the world food system (Bonnet et al., 2011). We are trusted advisors of our farming clients and largely considered by the public to be custodians of animal welfare. The British Veterinary Association (BVA) recognised that in order to fulfil these roles, we should be supporting citizens to make informed choices regarding farm animal welfare, but that few members of the public fully understand the food assurance labels that are designed to help them (Duffy et al., 2009). Therefore, the BVA devised an infographic to compare a number of UK assurance schemes in a simple to understand format, in terms of the BVA’s seven priority areas, including welfare at slaughter, use of antibiotics and measures to protect the environment.

The result is the chart shown in Figure 3, explaining the differences between the selected schemes. Most notably, this chart highlights the fact that all but two assurance schemes allow the confinement systems that prevent sows and laying hens from performing ‘normal behaviour’. In fact, the schemes that certify the majority of British animal produce allow confinement.

The Five Freedoms were formulated by Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) in the 1970’s, and are now well recognised internationally. In accordance, UK legislation and farm assurance schemes have traditionally focused on limiting some of the negative aspects of welfare featured in the five freedoms. However, over time, our aims have shifted from not just alleviating negative experiences for animals in their farmed environments, but to facilitating the expression of positive psychological wellbeing.

FAWC recently proposed that the minimum standards of farm animal welfare should move beyond the assessment of the Five Freedoms to achieve a ‘life worth living’, and as an aspirational standard, introduced the concept of a ‘good life’ in 2009. To experience a ‘life worth living’, animals should experience interest, comfort, pleasure and confidence (Mellor, 2016). To this end, animals on commercial farms can be provided with varied resources such as bedding and foraging substrates, exercise areas and enrichment objects that they can choose (Edgar et al., 2013).

But most of the schemes featured in the BVA’s infographic allow the confinement systems that impede the normal behavioural repertoire of farrowing sows. Use of the farrowing crate for four to five weeks in the periparturient period prevents foraging and nest making in farrowing sows, which can lead to stress, frustration and stereotypic behaviours. In the video below by Freefarrowing.org, you can see a free-range sow with the resources for nest building on the left, and a sow in a farrowing crate attempting to nest build on the right. Despite the provision of straw, the sow on the right cannot fulfil her behavioural needs.

In order to facilitate normal behaviours in pigs, and the opportunity to live a ‘life worth living’ or ‘a good life’, we can provide them with a constant supply of manipulable materials and toys, fibrous foods, deep substrate for rooting, and the space to move around in their environment and perform synchronous lying behaviours (Mullan et al., 2011). Supporters of farrowing crate systems argue that this pen infrastructure was designed to reduce laid-on piglet mortality, and coupled with genetic selection of sows for litter size, represents a highly efficient pig production system. However, genetic selection for maternal behaviours (Andersen et al., 2005) and slightly smaller litter sizes of larger piglets can help to improve survivability of piglets in free-farrowing systems, and can facilitate normal behaviours in commercial production.

In summary, I believe that all assurance schemes with an animal welfare component should be putting in to practice our long-held scientific understanding of animal welfare, embodied in the frameworks of the five freedoms and the ‘good life’ – and phase-out all confinement systems to enable species-specific behavioural opportunities as a necessity, not a luxury.

And as vets, I believe it is time for us to be constructively critical about the systems deployed to farm the animals under our care, and support a shift towards those that generate balanced outcomes for all aspects of animal welfare, including physical health and psychological wellbeing. Because – as highlighted by the #ChooseAssured campaign – when it comes to facilitating normal, species-specific behaviours, the most prevalent standards for farm animal production in the UK are falling short of our ambition to provide a “good life” for all animals.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] NFU Online | ||||

| (2014) | UK leads the way in animal welfare | [accessed 22.05.2019] | ||

| [2] Brexit: farm animal welfare | ||||

| (2017) | Summary of conclusions and recommendations. UK Parliament | [accessed 22.05.2019] | ||

| [3] The Grocer | ||||

| (2018) | What shoppers think about meat-free and plant-based, explained in 12 charts. | [accessed 22.05.2019] | ||

| Andersen, I.L., Berg, S. & Bøe, K.E. | ||||

| (2005) | Crushing of piglets by the mother sow (Sus scrofa) - purely accidental or a poor mother?. Applied Animal Behaviour Science | 93 (3–4): 229-243 | ||

| Bonnet, P., Lancelot, R., Seegers, H. and Martinez, D. | ||||

| (2011) | Contribution of veterinary activities to global food security for food derived from terrestrial and aquatic animals.. OIE 79th General Session World Assembly | Paris 22-27 May 2011. OIE, Paris. P 15. | ||

| Duffy, R. and Fearne, A. | ||||

| (2009) | Value perceptions of farm assurance in the red meat supply chain.. British Food Journal | 111 (7): 669-685 | ||

| Edgar, J., Mullan, S., Pritchard, J., McFarlane, U., Main, D. | ||||

| (2013) | Towards a ‘Good Life’ for farm animals: Development of a Resource Tier Framework to Achieve Positive Welfare for Laying Hens.. Animals | 3:584-605 | ||

| Mellor, D. | ||||

| (2016) | Updating Animal Welfare Thinking: Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” towards “A Life Worth Living”.. Animals | 6(21) | ||

| Mullan, S., Edwards, S.A., Butterworth, A., Whay, H.R. and Main, D. C. J. | ||||

| (2011) | A pilot investigation of possible positive system descriptors in finishing pigs.. Animal Welfare | 20: 439-449 |