IAV-S Elimination in Breed-to-Wean Herds is Challenging - but Possible

Influenza A virus in swine (IAV-S) continues to present an ever-changing health challenge in breed-to-wean populations.The impact of influenza on sows may be low, but it can take a toll when suckling pigs contract the infection from their dams. It can be difficult to get affected pigs off to a good start after they’re weaned. In one study, the cost per head due to losses such as mortality, culls and tail-enders was $3.23.1

IAV-S can also lead to variability in weaning weights. This, coupled with frequent co-infections of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, drive producers to request that aggressive steps be taken to eliminate influenza from their breed-to-wean populations.

Recent surveillance of growing pigs in the Midwest demonstrated that 90.6% of rural farms were positive for IAV-S at least once, based on monthly testing for 12 to 24 consecutive months.2 Introduction of replacement gilts and infection in suckling pigs played a key role in transmission of the virus, allowing it to frequently become endemic with only minimal clinical signs.

Points to remember

During the initial introduction of IAV-S, the virus will move and transmit readily and infect susceptible animals on the farm. In naive populations, IAV-S is highly contagious and spreads quickly.

Immunity to the influenza virus varies within a herd of growing pigs due to maternal antibody variation. In a breed-to-wean population, the prevalence of coughing is generally low among suckling pigs older than 14 days of age. In fact, the prevalence of coughing is only 2% to 5% when the pigs are weaned, but then it often increases as maternal antibodies decline and transmission occurs.

It’s important to remember that when piglets with maternally derived antibodies are challenged with a homologous strain — the same or similar strain — they will successfully eliminate the virus. However, when piglets are challenged with a heterologous strain — a different IAV strain than the one circulating — they can still actively shed the virus even if they have reduced clinical signs.

Studies suggest that IAV-S can circulate for 42 to 69 days in a closed population.3 This suggests that if the goal is to eliminate IAV-S, herds should be closed for at least 10 weeks. It might be better to provide a margin of safety by closing the herd for 12 weeks.

Even if the virus is eliminated, there’s the potential for re-introduction through human-to-pig contact, by aerosol transmission or endemic circulation.

Elimination plan

The approach to eliminating endemic influenza in breed-to-wean populations is a work in progress and lacks standardization. Strategies include natural virus circulation, mass vaccination of the breed-to-wean population, pre-farrow group vaccination or various combinations of these strategies.

At our practice, however, we’ve helped producers eliminate IAV-S with the following protocol and procedures:

- Identify the virus in the population.

- Identify which vaccine provides an IAV-S strain that’s homologous to the one circulating in the population.

- Vaccinate sows with the IAV-S vaccine within 6 weeks of farrowing using two doses administered 3 weeks apart.

- Limit the movement of pigs to within the farrowing room. Cross-fostering of piglets can occur on day 1 of age but only in the same room for those first 24 hours.

- Allow pigs to suckle colostrum from their own dam on day 1 of age before cross-fostering.

- Take measures to prevent IAV-S contamination from equipment used in multiple farrowing rooms such as split-suckle boxes, hot boxes and processing carts.

- Discontinue continuous pig flow within the site. For instance, stop using a holding room for weaned pigs due to be moved, and adjust delivery schedules so pigs are moved directly from sows to grow-finish units.

- Wean early — at 16 to 18 days of age.

Determine success

The success of an IAV-S elimination program can be determined by repeated nasal swabbing of due-to-wean pigs. Typically, 20 pooled nasal swabs with five pigs per swab are obtained every 2 weeks, initiated 6 weeks after the first vaccination. Oral-fluid samples are also collected from the growing gilt population to make sure there’s no ongoing IAV-S circulation.

Clinical signs of influenza as well as related costs of the disease should diminish and cease, but don’t forget that elimination doesn’t prevent re-infection. It’s imperative that biosecurity procedures be kept in place.

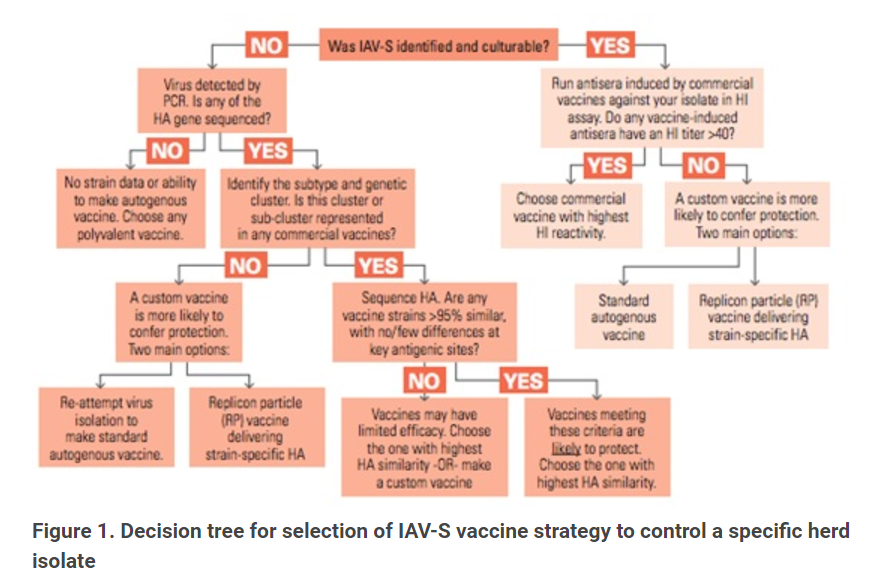

The American Association of Swine Veterinarians, along with USDA and other organizations, have devised a handout outlining the use of diagnostics and vaccines to control influenza; it includes a decision tree (Figure 1)4 that can provide useful guidance and a pathway for development of a strategy.

Figure 1. Decision tree for selection of IAV-S vaccine strategy to control a specific herd isolate

[1] Haden C, et al. Assessing production parameters and economic impact of swine influenza, PRRS and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae on finishing pigs in a large production system. . In: The 2012 proceedings of the annual meeting of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians. 75-76.

[2] Connor J, et al. Management and challenges of dealing with swine influenza. In: The 2013 proceedings of the Allen D. Leman Swine Conference.

[3] Lower AJ. Successful strategies for pushing SIV out of sow farms. American Association of Swine Veterinarians. In: The 2012 proceedings of the annual meeting of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians.

[4] A review of Optimal use of Diagnostics and Vaccines for Control of Influenza A Virus Infection in Swine. http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/pdf/a-review-of-optimal-use-of-diagnostics-and-vaccines-for-control-of-IAV-S-veterinarian-handout Accessed April 17, 2017.