Retailers setting their sights on pain management in pig production

Although antibiotics and sow housing have remained center stage in recent years, retailers are increasingly are putting pressure on producers to address pain management as part of their responsible-sourcing policies.In 2014, for example, Starbucks announced it would require pain mitigation with physical castration throughout their supply chains in the US. [1] Pointing to its animal welfare policy, which says farm animals should be free of pain, food and beverage giant Nestle said it was “committed to eliminating” surgical castration and tail docking.[2]

General Mills later announced in its animal welfare policy that it was studying the issue of pain relief in pigs as well as the potential elimination of castration.[3]

In its 2015 animal welfare policy — one of the most comprehensive of its kind — Wal-Mart announced that it was asking its suppliers to “implement solutions” to address such issues as castration without pain management.[4]

Most recently, pain management was on the agenda at the National Pork Board’s (NPB) inaugural Pig Welfare Symposium in November in Des Moines.

One thing’s for sure: Initiatives to promote pain mitigation are on the horizon — a trend that eventually could change the way pork producers castrate males to prevent boar taint or whether they do it at all.

Tricky spot

David Pyburn, DVM, senior vice president of science and technology at NPB, notes that commercial pork producers are trained to castrate baby male pigs with minimum pain and infection.

Some producers acknowledge that it’s a decision that’s being made at other levels, namely retailers trying to get a jump on emerging concerns over physical castration.

It’s a tricky spot for producers. On one hand, there are forces that want anesthetics used with physical castration — even though neither the FDA nor the USDA has approved the use of anesthetics in food animals.

“There’s been lots of chatter about using local anesthetics, which is not a good alternative; even with anesthetics the pigs aren’t pain-free,” says Indiana-based consultant Larry Rueff, DVM, who oversees the health programs of farms with an annual production of approximately 2 million pigs. “Local anesthetics generally take some time to have an effect before the procedure, which can make it challenging to implement in a busy production setting,” he adds. “Typically, they also wear off within 60 minutes.”

For producers, there’s also the continued risk of bacterial infection or higher mortality associated with physical castration — a heightened concern now that producers are also being asked to reduce or eliminate antibiotics from production. Rueff notes that traditionally-raised barrows, or castrated pigs, typically have a 1%-2% higher mortality rate than gilts.

Costs of castration

No recent studies have been conducted in the US to assess the cost of castration with or without anaesthetics. However, in a 2015 Spanish study sponsored by Zoetis and conducted by PigChamp with nearly 3,700 male pigs, researchers found that the cost of one male weaned pig is $1.23 higher for castrated pigs with topical anaesthetic compared to intact pigs.

To determine the cost of castration, researchers included the cost of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug meloxicam ($18.54/100 ml, with 0.04 ml administered per piglet); the cost of topical antibiotic spray ($6.36/200 ml, with about 1 ml administered per piglet); and the labour cost ($29.57/hour per worker). They concluded that workers require about 1.5 hours to castrate 100 piglets, including the meloxicam administration (30 minutes before conducting the surgical procedure).

Hard costs aside, the researchers also found that physical castration leads to growth- and mortality-related costs.

For example, although castration did not affect performance of light or medium piglets, heavy castrated piglets (5.62 pounds at birth) tended to have a lower average daily gain (0.52 pounds or 237.4 grams per day) and had a lower body weight at weaning (17.2 pounds, compared to 17.57 pounds in intact males).

Additionally, mortality for light- (12.72 pounds) and medium- (14.96 pounds) weight castrated piglets was almost double that of intact piglets.

Higher mortality

In 2009 researchers at the European Symposium on Porcine Health Management in Copenhagen, Denmark, presented results from a meta-analysis of 15 European field studies in 10 different countries. They tracked the data on 4,540 pigs through slaughter (2,274 physical castrates and 2,266 immunocastrated pigs) and found that mortality in suckling pigs is 39% higher in castrated pigs compared to immunocastrated pigs. They also reported that castrated piglets tend to have a higher incidence of postoperative secondary infections, arthritides and hernias.

Infection from castration varies significantly from farm to farm, and the actual cost to castrate on a farm is “very small,” Rueff adds. Additionally, producers likely would not reduce the labor significantly because they still would be picking up the pig for other reasons other reasons, such as vaccination or tail docking, which is common on most US swine farms.

Although producers point to the low rate of infections, castrated pigs typically are not given pain medications. Despite the low cost of pain-mitigation medication (approximately 40 cents according to André Lavergne, who tracks the certifications and audits on farms supplying Certified Humane producer Les Viandes duBreton Inc. in Rivière-du-Loup, Canada), producers say the additional labor isn’t worth it.

Lavergne says that applying lidocaine adds 25% to the time it takes to castrate. In the US, lidocaine has not been approved for veterinary use, but the American Association of Swine Veterinarians recommends the use of analgesia and/or anaesthesia if pigs are castrated after weaning (typically ranging from 17 to 28 days).[5] The American Veterinary Medical Association recommends the use of analgesia and/or anaesthesia if pigs are castrated after 14 days of age.[6]

Even the Department of Health and Human Services has weighed in, recommending in a 2014 letter to the National Pork Producers Council extra-label drug use in food-producing animals. Daniel McChesney, PhD, director of the Office of Surveillance and Compliance’s Center for Veterinary Medicine at the FDA, wrote: “We consider the use of analgesics and anaesthetics for the purposes of alleviating pain, suffering and discomfort in animals as an acceptable justification for using approved drugs in an extra-label manner.” [7]

Still, questions remain.

“The biggest question about IC is how consumers will view it: like a vaccine, which it is not; like chemical castration, which it is not; or something like a GMO?” Lavergne asks.

Physical castration practices carry a host of risks, including infection at the site of incision, transmitting bacteria from pig to pig, hernias and even failure to remove both testicles.

“You’re affecting biosecurity, animal safety, human safety,” says consultant Erika Voogd, former corporate quality-assurance manager for McDonald’s supplier OSI Industries Inc. and one of that retailer’s original animal welfare auditors. “You’ve got to consider your aseptic practices. “Do I think it’s a traumatic procedure for a baby? Yeah. Do I think there’s a risk if you don’t do it right? Yeah.”

Pyburn says the pork industry has made progress on addressing the pain and stress associated with physical castration. Its “Swine Care Handbook” addresses moving the procedure to an even younger age, such as 3 to 7 days old (down from the average of 4-14 days old). NPB researchers found that stress as a result of castration is shorter at a younger age.

“Whether you castrate pigs or not, you’re still picking them up for tail docking,” says Collette Kaster, executive director at the non-profit Professional Animal Auditor Certification Organization, which certified auditors for the Common Swine Industry Audit. In the end, she adds, “The biggest question is still pain management.”

Option on the table

Although the jury is still out on how to best manage pain associated with tail docking, there is already a promising option for eliminating pain that goes with castration — immunocastration (IC). If there’s any pain associated with this practice, it’s the momentary prick from a needle.

IC involves administering a protein compound that works like an immunization, stimulating pigs’ immune systems to temporarily block testicular function and inhibit accumulation of androstenone and skatole, the naturally occurring compounds that cause boar taint. A first dose is given around 9 weeks of age to prime the pig’s immune system, followed by a second dose during the finishing period, typically 4 to 6 weeks before the pigs go to market, although the period can be varied depending on the type of carcass composition desired.

The technology has been approved in more than 60 countries, including the European Union, China and Brazil — where it’s been used for a decade. Although approved for use in the US in 2011, the technology has yet to gain traction with the US pork industry, largely because most packers simply won’t accept intact males.

Then there’s the matter of proving the intact males were immunocastrated properly and assuring packers that boar taint won’t be an issue with these animals. Between the documentation that’s required to certify that the intact boars were immunocastrated and the overhead associated with the two-dose injection procedure, “some smaller producers won’t use it [for economic reasons],” says John McGlone, PhD, professor at Texas Tech University. In 1988, he authored one of the industry’s first scientific papers on the pain associated with castration.

With IC, the payback is big: immunocastrated barrows generate a potential increase of $5.32 per head in net income (after product and administration costs of $5 per head).[8]

Return on investment

“[With IC] there is a return on investment. It’s an economically viable alternative,” McGlone says of the improved feed conversion and average daily gain associated with immunocastrated pigs.[9]

By the same token, he continues, “If you use [pain mitigation] with physical castration, there’s no return. The pig won’t grow faster or die less, so consequently it depends on your particular company’s pressures from the public.”

Like antibiotics used for managing disease or improving herd efficiency, IC is a technology that’s regulated and approved by FDA but nevertheless makes some retailers uneasy because of consumer misconceptions. Hence, the focus is on pain mitigation instead of a wholesale shift to IC as an alternative to castration.

Supporters of the technology acknowledge that the scientific literature of immunocastration should be converted into language that the public can understand — something that can be digested by both consumers and retailers alike — for it to be accepted on a larger scale.

None of the retailers contacted for this report — Wal-Mart, Kroger, Publix and Whole Foods — responded to multiple queries by Pig Health Today.

“The question retailers are asking both producers and plants is: ‘We know castration hurts; what are you going to do about it?’” McGlone adds. “They have no preferred solution; they just want the problem fixed without causing other issues.”

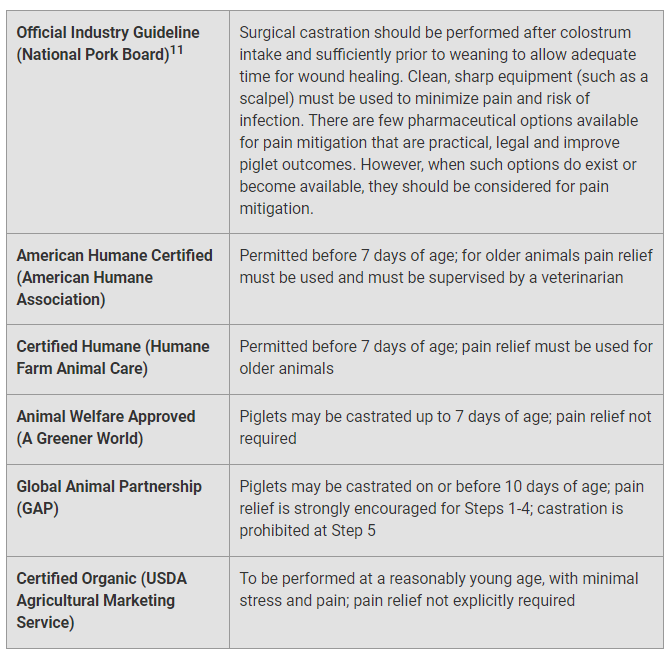

Standards for piglet castration[10]

Sources: Swine Care Handbook; Animal Welfare Institute, July 2017

References:

1. http://globalassets.starbucks.com/assets/313ef95924754048b3ca8cea3cc2ff90.pdf (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017).

2. http://www.nestle.com/csv/communities/responsible-sourcing/meat-poultry-eggs (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

3. https://blog.generalmills.com/2015/07/reaffirming-our-commitment-to-animal-welfare/ (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

4. https://corporate.walmart.com/_news_/news-archive/2015/05/22/walmart-us-announces-new-animal-welfare-and-antibiotics-positions (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

5. https://www.aasv.org/aasv/position-castration.php (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

6. https://www.avma.org/KB/Policies/Pages/Swine-Castration.aspx (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

7. https://www.aasv.org/documents/FDA_Pain_Mitigation_Response.pdf (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

8. Buhr BL, Zering K, DiPietre D. A comprehensive, full chain and US meat sector economic analysis of the adoption of Improvest® by the US pork industry. Am Assoc Swine Vet 2013; 189-194.

9. Cowles B, Meeuwse D, Bradford J. Data summary of immunological castration impact in grow-finish performance of male pigs in USA. Am Assoc Swine Vet 2013; 375-376.

10. https://awionline.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/FA-AWI-standardscomparisontable-070816.pdf (Date of access: Oct. 26, 2017)

11. This section was updated by the National Pork Board, December 2017, for the benefit of this report. All other columns were provided by the Animal Welfare Institute.