African swine fever in wild boar: measuring numbers

Assessing wild boar population sizesEditor's note: the following is an excerpt from African swine fever in wild boar populations - ecology and biosecurity. It was created by the FAO, WOAH and European Commission. Additional content from the booklet will be shared as an article series.

One difficulty with the sustainable management of wild boar lies in assessing population sizes. Even if official statistical hunting data are available for most countries, their reliability is often questionable. Scientists and practitioners have developed many different methods of measuring the relative abundance of wild boar in particular natural zones or habitats, but there is no standardized reproducible approach that could give comparable results on larger spatial scales, fit all situations and be logistically feasible and cost-efficient (Engeman et al., 2013). Existing population estimates differ by methods, timing, accuracy and reliability from country to country, and even within the same country.

For example, in countries with stable snow cover, approaches such as track counts with correction indexes and closed transect surveys repeated two to three times are often used. These approaches can be supplemented with, for example, counts at the feeding locations, driven counts (especially in snow-free areas) and camera traps. In other countries, only hunting bag statistics are available for analysis as a relative measure of wild boar abundance. Census data from hunting grounds are usually self-reported by hunters and gamekeepers, who are not always adequately coordinated and trained to carry out such surveys using standardized methods.

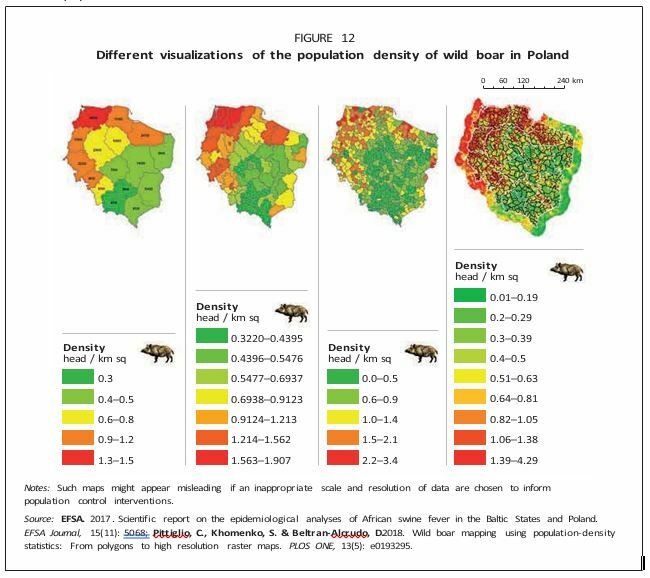

Furthermore, population data obtained with a mixture of unreliable methods are routinely summarized for administration purposes to give a generalized picture for a country or region at some level of aggregation, as shown in Figure 12. Interpretation of such aggregated statistics can be very misleading, as it shows averaged (normalized or levelled) wild boar population density estimates; these can be acceptable metrics of relative abundance for comparison with other areas, but are not very helpful for informing decisions or management interventions on the local scale.

For this reason, whichever census methods are used, wild boar population data should be collected and analysed at the highest spatial resolution possible, preferably at the level of individual hunting grounds as the smallest census and management units. Sufficient granularity of population data is a particularly important prerequisite for developing realistic interventions for wild boar populations in ASF-affected areas. Hunting communities should be encouraged to collaborate with wildlife biologists and experts in wildlife disease epidemiology in order to improve their monitoring methods and obtain more objective, reliable and comparable population estimates.

Wild boar: how many are “too many”?

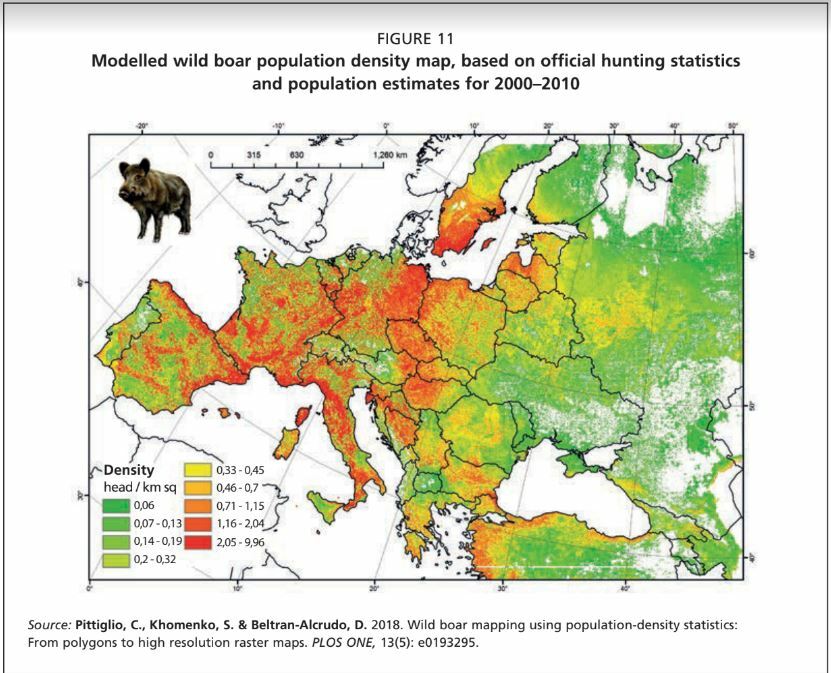

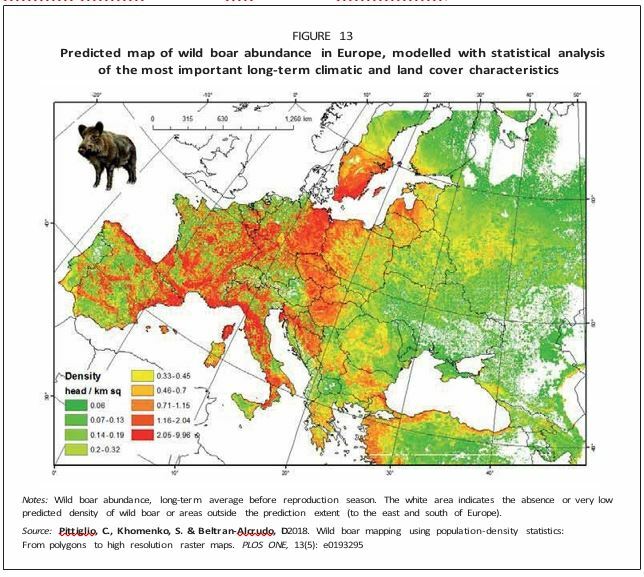

The ecological capacity of habitats varies widely across Europe and is dependent on environmental conditions. The situation is also complicated by a high level of habitat transformation, the seasonal availability of crops, climate and weather change patterns, and hunting management practices. Studies suggest that the main factor naturally limiting wild boar abundance is winter temperature (Melis et al., 2006). The warmer the winter conditions, the higher and more stable the population of wild boar (Figure 11 and Figure 13). Water availability is another factor limiting wild boar abundance in more arid climates (Danilkin, 2002). However, long-term climatic and land cover characteristics can only explain approximately 50 percent of the variation in wild boar population abundance (Figure 13), while the rest is mainly related to in situ factors such as population management, food availability and seasonal variability of climatic conditions (Pittiglio, Khomenko and Beltran-Alcrudo, 2018). Due to the extensive distribution and high ecological plasticity of wild boar, there is no standard or average density that can be universally recommended as “optimal” across Europe. Wild boar have evolved as a species adapted to seasonally (and sometimes for longer periods) varying feeding resource availability, such as changes in beech and oak productivity (Groot Bruinderink, Hazebroek and Van Der Voot, 1994; Selva, Berezowska-Cnota and Elguero-Claramunt, 2014).

Local variations within a range of some 60 percent of their average pre-reproduction numbers are a common occurrence, dependent on such factorsas weather conditions, habitat productivity, hunting pressure, predation and disease (Bieber and Ruf, 2005). For example, under the conditions of predictable climate and without artificial feeding, an average long-term population density of 1.0 head/km2 would fluctuate within the range of some 0.7–1.3 head/km2. Sharp year-on-year variations in animal density are particularly characteristic for northern populations, which are strongly impacted by climatic factors. However, in the last few decades, over most of Europe, wild boar demonstrate positive long-term population trends (Massei et al., 2015).

Guberti, V., Khomenko, S., Masiulis, M. & Kerba S. 2022. African swine fever in wild boar – Ecology and biosecurity. Second edition. Chapter 2. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 28. Rome, FAO, World Organisation for Animal Health and European Commission. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0785