The age of digital epidemiology: tracking ASF worldwide

With ASF an immediate threat to European swine herds, the virus is being tracked and predicted on a daily basis using epidemiological tracing technology.How have we traced ASF so far?

The International Disease Monitoring (IDM) team is an important group within DEFRA’s Animal & Plant Health Agency (APHA). Their function is to keep an eye on exotic new and notifiable animal diseases around the world and make assessments of the risks that they pose to the UK’s livestock industries. They provide advice and recommendations to APHA and wider government on this subject as well as publishing information for the general public.

Intelligence data is gathered from a number of sources including official reports to the OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) and the EU (European Union). EU member states with exotic notifiable disease outbreaks make regular presentations to the Animal Health and Animal Welfare section of the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed (SCoPAFF). This information is regularly reviewed by the IDM team. They also use unofficial sources such as Pro-Med e-mail alerts, local media reports and personal contacts which provide the remainder of the information and help to give an accurate picture on the ground.

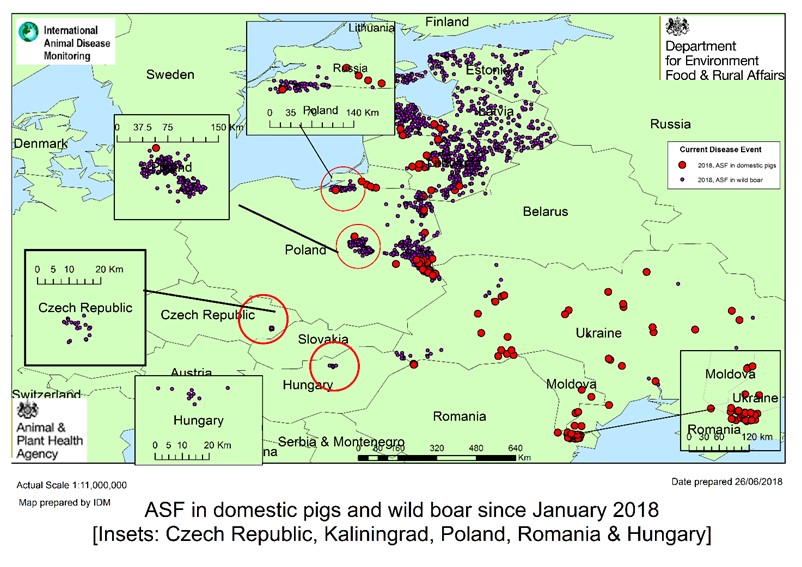

In the case of African Swine Fever (ASF) the official reporting system provides the basis for regularly updated maps of the westward spread of disease across Europe from the Caucasus area over the past 11 years. The latest map is shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1: Map of ASF cases Jan – Jun 2018

These maps show recent confirmed cases of disease in domestic pig herds and feral wild boar, which are also being proactively sampled and tested for ASF. Some EU countries pay hunters to shoot and submit wild boar carcases, while others just rely on finding dead animals to test. There are more wild boar carcases submitted in EU member states because there is an active surveillance programme in place. Some other countries outside of the EU have lower levels of surveillance and case numbers are reduced as a result. This doesn’t mean that they are free of disease, just that it has not been detected and reported. It is important to bear this in mind when viewing the map in Fig 1.

As can be seen, there have been some long-distance jumps of disease and in these cases, human involvement is suspected as the most likely transmission route. This may have been through indirect spread by vehicles or equipment, or more likely, by the inadvertent feeding (or scavenging) of infected meat products to wild boar.

What would we do in the event of an outbreak in Britain?

If an outbreak of disease was detected in the Great Britain, pigs on the affected farm would be culled out immediately and epidemiological investigations initiated. This situation is covered by the various country Exotic Disease Control Strategies which state that movement restrictions are immediately imposed on suspect premises and if disease is confirmed, Protection and Surveillance zones will be applied. Links to country-specific strategies are as follows:

One of the first on-farm actions that would be undertaken is the blood sampling of a proportion of the different groups of pigs on the infected premises (IP) at slaughter. By looking at the levels of virus and antibodies present in the samples, a picture would emerge of the order in which the groups had been infected and approximately when the virus had entered the pig herd.

Armed with an estimate of when the disease is likely to have entered the herd, disease tracings time windows can be identified. Tracings would be initiated for both the potential source and spread of infection. In other words, we would want to find out where the virus had come from and where it might have gone to.

Tracings deal with many different potential pathways and this is especially important with ASF virus, as it can survive in the environment for several days. As a result, we would want to trace vehicles, equipment, manure, carcasses and people; as well as, and most importantly, any live pigs that had left the IP during the spread tracing window. In the case of source tracings, we would also be looking at movements of similar items (pigs, vehicles, equipment, visitors) onto the premises during the potential source tracing window. In addition, this would include a check for any feeding or access to infected meat products, as well as usual sources of feed and bedding, and an assessment of wildlife in the area. A final route to consider would be semen for artificial insemination purposes, as this too can contain ASF virus.

How can producers help?

There are a number of ways in which pig producers can assist APHA vets with their investigations and these are listed below –

By keeping accurate and up-to-date records of:

- Movements of live animals on and off the premises (legal requirement).

- Movements within the premises or pyramid.

- Movements of carcasses.

- Where and when manure or slurry has been spread.

- Movements of lorries – feed/bedding/livestock/deadstock.

- All visitors and their vehicles – delivery drivers/vets/fieldsmen/electricians/pest controllers etc.

- Records of feed and bedding suppliers.

- An updated staff list with contact details.

- Details of porcine semen deliveries or despatches.

It is also helpful if pig farmers can take a look at their own farm premises with regard to biosecurity and consider the following questions:

- Do people and vehicles clean and disinfect both on and off?

- Can wildlife access buildings? E.g. rodents / birds and larger mammals.

- Can wildlife access grazing in outdoor units? E.g. rodents / birds / larger mammals.

- Are there specific risk factors in the local area? E.g. municipal dumps / footpaths / picnic sites / laybys / Eastern European workers or visitors / local populations of feral wild boar.

- Do staff have contact with pigs on other premises? Or keep pigs of their own?

- Do deadstock collection vehicles enter the farm, or collect from the boundary?

- Are incoming pigs quarantined before mixing with resident stock?

- Are pigs or semen imported?

Although many of these factors cannot be altered, the knowledge of their existence could help APHA staff in their investigations and will also alert pig producers to the fact that they face a greater risk of acquiring disease. This, in turn, may lead them to change their business model, if appropriate, to address these concerns.

The current 21-day standstill for pig movements should help curtail the rapid spread of disease between premises, however, it does not apply within registered pig pyramids. Therefore, it is important that producers recognise disease signs early and report their suspicions to APHA rapidly. The prompt reporting of movements through the eAML2 electronic system (in England and Wales) and ScotEID (in Scotland) is another key disease control feature that should facilitate the tracings process.

A campaign to highlight the dangers of swill feeding has recently been launched. It is important to remind the public that any feeding of meat products, including the feeding of swill, kitchen scraps and catering waste to any pigs, including pet pigs, wild boar or feral pigs, is illegal.

.png)

Although the example given here involves ASF, pigs are susceptible to other exotic notifiable infectious diseases. Many of the biosecurity factors and useful records listed above would be invaluable in the control of these diseases too.

In conclusion, it is important for everyone to work together when combating notifiable disease incursions into the national pig herd in order to preserve our current high level of pig health and welfare and our international trading status. I hope this article has helped you to identify how and where your involvement can make a difference.

Jo Wheeler, Veterinary Advisor at APHA

Jo works as South West Field Epidemiology Veterinary Advisor for APHA and is a member of a national team which gives epidemiology advice when there is an outbreak of any notifiable disease.