The Problem of Lameness on Irish Pig Farms

Amy Quinn and Julia Adriana Calderón Díaz of Teagasc conclude that lameness is a major production disease in pigs of all ages on Irish farms.Prevalence of Lameness

In a recent survey involving 68 Irish pig farms, the authors established the prevalence of lameness in finishers, replacement gilts and loose housed pregnant gilts and sows (Figure 1). This was achieved by scoring the pigs’ walking ability from 0 to 5 according to severity (0 = sound and 5 = severely lame). All animals receiving scores >1 were considered lame.

In total, 643 finishers of 18 weeks of age and 646 finishers of 22 weeks of age, 525 replacement gilts, 518 pregnant gilts and 604 pregnant sows were inspected.

The researchers found high levels of lameness in all classes of pigs confirming that lameness is a major production disease on Irish farms.

Economics of Lameness

From an economic point of view, lameness reduces the productivity of a unit by:

- reducing sow longevity by increasing the involuntary culling rate of sows

- reducing the number of pigs produced per sow per year

- increasing expenses as a result of the cost incurred in replacing sows, increased work load and treatment expenses and

- reducing the numbers of finisher pigs reaching the factory.

The latter occurs because an increase in the rate of sow culling results in a decrease in the average age of the herd and younger animals produce smaller litters.

Currently, in Irish pig herds almost 50 per cent of sows are culled before they reach the 3rd parity. As a sow does not become profitable until after she has had her 3rd litter, this means that currently 50 per cent of sows do not ‘pay for themselves’. A 1997 survey by Laura Boyle found that almost 70 per cent of sows culled for lameness had not produced a fourth litter. Hence, lameness is a substantial contributor to the premature culling of sows and young sows in particular are more susceptible. In herds with a young parity profile due to premature culling for lameness, there is a reduction in the number of pigs weaned per year because younger animals yield fewer pigs per litter than sows. This ultimately reduces the number of finisher pigs reaching the factory and farm income.

Culling for lameness is probably underestimated by producers because animals that are culled for poor body condition or reproductive failure are often lame too. Indeed, lameness is likely a major driver of poor reproductive performance and infertility in sows. In a high proportion of lame sows, internal infectious and inflammatory responses, i.e. the immune system, associated with pain are activated. This is very costly in terms of energy. Furthermore, the inflammatory process changes amino acid metabolism and the sow’s amino acid requirements with proline and phenylalanine becoming more important than lysine. This explains why a lame sow could consume the same amount as a non-lame sow but be in a poorer body condition. She is simply not utilising the nutrients consumed properly or efficiently.

Furthermore, products of the inflammatory response such as cytokines are not only involved in connective tissue degradation, which exacerbates the lameness problem but also disrupt the hormones controlling reproduction leading to poor fertility. This is why lame sows produce at least 1.5 fewer litters than sound sows during their productive life.

Poor mobility and pain caused by lameness results in reduced lactation feed intake, which has an indirect negative impact on the future performance of the litter and on the sow’s subsequent reproductive performance. Poor mobility also increases the likelihood of piglets being crushed. Indeed piglet losses due to crushing by lame sows are 15 per cent higher than from sound animals.

The extent of the expenses associated with treating lameness in sows is firstly dependent on whether or not any veterinary action is taken. Often with lame sows the only ‘treatment’ is to cull after production of the litter. It is less regular that lame sows are euthanised. In the 1997 culling survey, lameness was responsible for 11.3 per cent of sow removals in a study on a sample of Irish commercial pig farms.

Similarly, a Swedish study found that lameness and foot lesions were responsible for 8.6 per cent of sow removals, with 32.1 per cent of these requiring euthanasia. It is worth noting that as it is illegal to sell lame sows in some Scandinavian countries the rates of euthanasia for lameness are much higher than in Ireland. With finishers, treatment more often includes antibiotics. Indeed lameness is the third most common cause for treatment with antibiotics in weaner and finishing pigs. Pain relievers are used much less often but all of these measures are associated with substantial costs, e.g. labour, drugs etc.

Causes of Lameness

Limb lesions

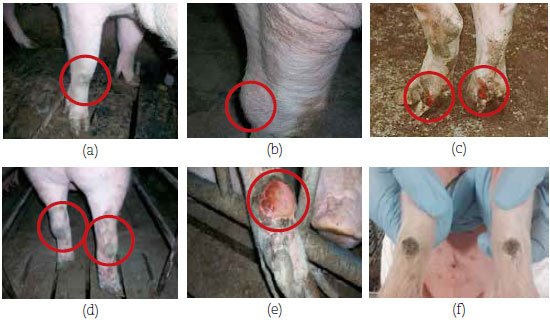

Injuries to the limbs may result in lameness. The most common limb lesions in weaners, finishers and sows are calluses, swellings, wounds, external abscesses and bursitis. Their severity can vary from mild to very severe (Figure 2, a-e).

Studies reported an increased risk of lameness associated with higher callus, bursitis and capped hock scores on the limbs of finishing pigs. It is difficult to say whether this is because limb lesions cause discomfort or because lame pigs spend more time lying and that this increases the risk of limb lesions. Limb lesions are highly prevalent in piglets with between 80 to 90 per cent of piglets being affected by lesions; largely skin abrasions to the front limbs (Figure 2, f).

Claw lesions

While a high proportion of sows (between 96 and 100 per cent) have at least one lesion present on each claw, claw lesions only account for between five and 20 per cent of sow lameness.

The relationship between lameness and claw lesions may be dependent on the location and seriousness of the lesion. Some areas of the claw are more sensitive than others meaning that minor lesions may not result in pain and, therefore, not cause the animal to be lame.

One of the major causes of injuries to the claws (and limbs) is fighting on concrete/slatted flooring at mixing. Even after the dominance hierarchy is established, pigs will continue to fight if they are overstocked or have to compete for access to feed, e.g. in long trough/floor feeding systems.

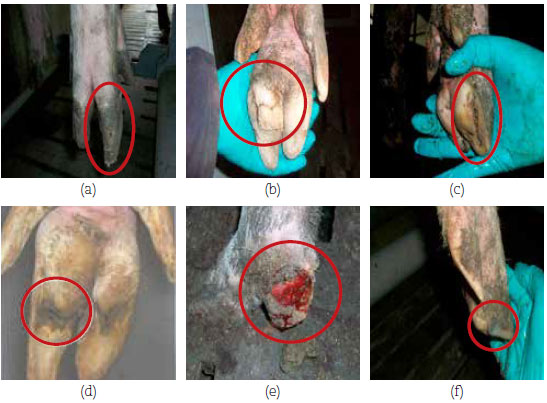

Injuries to the claws (Figure 3) and limbs commonly include partial or whole amputation of the dew claws, tearing of pre-existing areas of overgrowth in the heel or splitting of existing cracks in the weight bearing claws. In the absence of any treatment such injuries can become infected and, in extreme cases, lead to osteomyleitis (infection of the bone) and ultimately to death or culling. Claw lesions are thought to be more severe in sows than in weaners and finishers. There is also a high prevalence of claw lesions in piglets with sole bruising and erosion being among the most common lesions.

Osteochondrosis

Osteochondrosis is another major cause of lameness - and secondary degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis - in pigs. Osteochondrosis develops when areas of the growth cartilage (or growth ‘plates’ which are responsible for the growth of bones in length) experience restricted blood flow and die causing pain and lameness. It causes increased pressure on the surface of an affected joint in developing animals. It is most common and severe in the elbow joint of pigs however, unlike claw and joint lesions Osteochondrosis is difficult to diagnose in live animals.

Other causes of lameness include infectious arthritis, arthrosis and trauma to the limbs/fractures.

Risk Factors for Lameness

Housing type

Housing type is one of the major factors influencing lameness in commercial pig farms. It influences the amount and type of movements the pig can make. Individual housing in gestation stalls contributes to lameness via reduced bone strength and muscle mass, and joint damage due to lack of exercise. The EU Directive 2001/88/EC states that in all 25 member states 'Sows and gilts shall be kept in groups during a period starting from four weeks after the service to one week before the expected time of farrowing' since January 2013.

Group housing during gestation has several welfare benefits for sows, including greater freedom of movement which allows for exercise and social interactions. However, group housing also present some disadvantages such as fighting among newly mixed unfamiliar sows and injuries that could ultimately lead to lameness.

In a study conducted at the Moorepark Pig Unit, lameness, claw and limb lesion scores were compared between 42 multiparous sows housed in stalls and 43 sows kept in a single dynamic group with an electronic sow feeder during gestation. All sows were on concrete, predominately fully slatted flooring, although the group housed animals had solid floored lying bays.

Seventy-four per cent of group housed sows and 33 per cent of individually housed sows were lame on transfer to the farrowing crate (day 110 of gestation). Furthermore, the number of severely lame sows was higher among the group housed sows (Table 1). Additionally, group-housed sows had higher scores for claw lesions on the heel area such as heel overgrowth and/or erosion (Figure 4) and a higher risk of wounds on the limbs and swellings on the hind limbs (i.e. bursitis; Figure 2) than sows housed individually.

However, individually housed sows were at greater risk of a wider range of claw lesions including white line damage, horizontal cracks in the wall and dew claw injuries on the day of transfer to the farrowing crate.

| Table 1. Number of sows housed in individual gestation stalls or in a single dynamic group with an electronic sow feeder during gestation that received each lameness score on transfer to the farrowing crate at day 110 of pregnancy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lameness score | Group housing | Gestation stalls |

| 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 1 | 11 | 23 |

| 2 | 19 | 11 |

| ≥3 | 13 | 3 |

| Total | 42 | 43 |

These findings confirm that the problem of lameness in Irish sows will increase with the change to group housing systems. The main reason for this is the widespread use of fully slatted concrete flooring, minimal space allowances and competitive feeding systems all of which are associated with an increased risk of lameness.

Floor type

Flooring type can be a major influencing factor on lameness and claw health as the pig has continual contact with the floor surface. An ideal floor for pigs should be soft, clean, not slippery and not abrasive; the surface should be even and without sharp edges. It should not become deformed, deteriorate or demand high maintenance. Furthermore, it should minimise animal discomfort and the risk of injuries and provide the pigs with the opportunity of a normal gait.

In the majority of Irish pig units, slatted concrete floors are used and such floors increase the risk of lameness. Slatted floors present some disadvantages to the animals such as an uneven walking surface and the lack of bedding.

Finnish researchers found that sows housed on slatted floors were 3.7 times more likely to be severely lame compared to sows housed on solid floors. Softness plays an important role in physical comfort and softer floors like straw bedding or rubber mattresses are preferred to harder floors. However, the use of bedding is not compatible with modern intensive pig production systems. Rubber mattresses appear to be a good alternative to the use of bedding since it is comfortable and firm, dry and clean and has low thermal conductivity. Research from Moorepark showed that the use of rubber mats in farrowing crates improved the posture changing ability of sows by providing more comfort and better foothold on slatted steel (Tribar type) floors.

A more recent Moorepark experiment found that sows kept on slatted steel (Tribar) floors in the farrowing crate were at higher risk of heel overgrowth and/or erosion, heel sole crack and horizontal cracks in the wall than sows on cast iron flooring (Figure 5). These results are most likely related to the high void ratio associated with slatted steel floor types. If the void ratio is higher than 40 per cent, pigs weighing 100kg or more experience injuries in the heel region. This is likely due to the greater pressure applied to the claw when the area of contact of the foot with the ground is decreased.

The high void area associated with slatted steel/metal (Tribar type) floors is also a major contributor to limb and claw injuries in piglets. Injury to the coronary band often occurs when piglets feet slip between these slats or become caught in the slats. This injury is much less common with plastic/plastic covered woven wire floor types.

In farrowing crates, piglets commonly get skin abrasions to the front legs as they fight to establish the teat order on abrasive flooring. The majority of piglets have sole bruising and they may also incur sole erosion due to the abrasive properties of the floors used in farrowing crates. Indeed, the prevalence of skin and foot abrasions in piglets is positively associated with concrete flooring.

In the Teagasc lameness survey, researchers found a high prevalence of limb abrasions, sole bruising and coronary band damage in suckling piglets (Figure 6); most of these were strongly associated with piglet age. For example, the proportion of piglets affected by skin abrasions increased with age while the proportion of piglets affected with coronary band damage decreased with age. All of the lesions recorded were strongly associated with the presence of metal/steel slatted flooring in the farrowing crate. As such, lesions are a potential route for the entry of infection and are a welfare concern. The use of such flooring in farrowing crates should be re-considered.

For finishers, replacement gilts and pregnant sows we identified an increased risk of lameness associated with concrete slats having voids wider than 1.8cm. Finally, for finishers on farms where the pens were cleaned fewer than four times per year there was more lameness.

August 2013