China to adopt GM corn & soy: why it matters for South Africa

Chinese National Crop Variety Approval Committee clears the path for cultivating genetically modified (GM) cropsSomething important for global agriculture happened recently but received minimal media coverage. The Chinese National Crop Variety Approval Committee released two standards that clear the path for cultivating genetically modified (GM) crops in the country.

This has been the missing piece in the regulations for the commercial growing of genetically modified maize and soybeans in China. The government has two steps in these regulations. These are a “safety certificate” and a “variety approval” before crops can be commercially cultivated.

Various genetically modified maize and soybean varieties have received the safety certificate since 2019. What’s been missing has been the “variety approval”. Now that hurdle has been cleared and commercialisation of genetically modified crops in China is a real possibility.

This message was also echoed by the Chinese Agriculture Ministry. It noted that “China plans to approve more genetically modified (GM) maize varieties.” Currently, China imports genetically modified maize and soybean but prohibits domestic cultivation of the crops.

The change in regulations would potentially lead to an improvement in yields. This is aligned with China’s ambition of becoming self-sufficient in essential grains and oilseeds in the coming years. There are specific targets in products like pork, where the country wants to produce 95% of its consumption by 2025.

South African farmers and agribusinesses need to pay close attention to these developments because it will have an impact on the long-term growth of the domestic agricultural sector.

The increase in production in other parts of the world, specifically in maize, where South Africa is a net exporter, could bring increased competition and downward pressure on prices in the medium term. Some of South Africa’s key maize export markets are South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Vietnam. All have proximity to China.

If China progressively increases production and becomes a consistent net exporter of maize, South Africa would have to explore markets elsewhere. This would be a challenge.

The debate

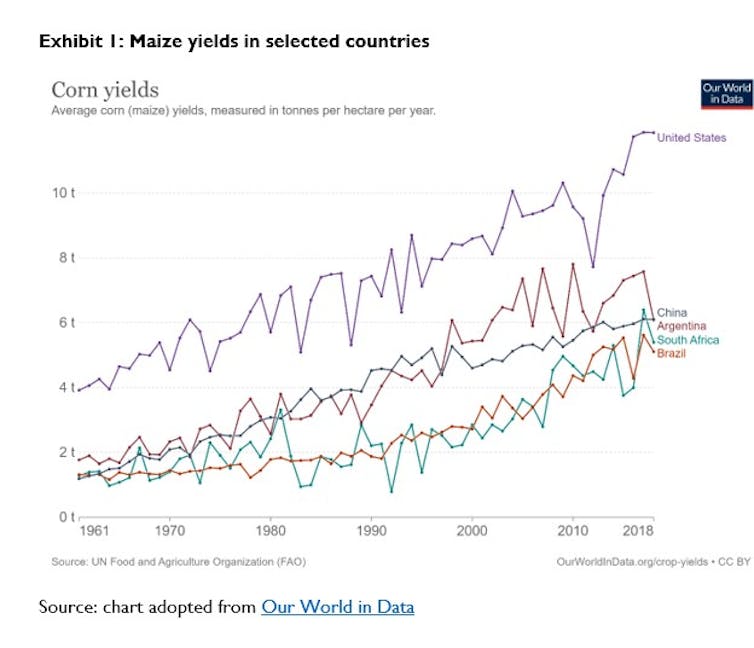

China’s maize yields are comparable with South Africa, the United States, Argentina and Brazil, which have long adopted the genetically modified seeds (see Exhibit 1).

In these countries, among others, genetically modified seeds have had additional benefits such as lowering insecticide use, encouraged more environmentally friendly tillage practices and crop yield improvements.

If maize and soybean yields improve in the coming years, China’s import dependence could lessen.

China is one of the world’s largest maize and soybean importers. The country accounted for 13% of global maize imports in 2021 and roughly 60% of the world’s soybean imports. Reducing import volumes is likely to lead to downward pressure on global prices.

A reduction in the global maize and soybeans prices would be positive for consumers and the livestock and poultry sectors. This is much needed as the world has been in a period of elevated food prices over the past two years.

This is unlikely to happen within the next two seasons as widespread planting of GM crops in China will likely take some time. China has been slow in GM adoption, but made significant progress in gene editing, which has different regulations, and has helped improve the crop yields.

The consequences

There are lessons here for the African countries, most of which have resisted the cultivation of genetically modified crops. South Africa is the exception.

According to the International Grains Council, South Africa produces about 16% of sub-Saharan maize, using a relatively small area of an average of 2.5 million hectares since 2010. In contrast, countries such as Nigeria planted 6.5 million hectares in the same production season but only harvested 11.0 million tonnes of maize, equating to 15% of the sub-Saharan region’s maize output.

Irrigation has been an added factor in South Africa, but not to a large extent, as only 10% of the country’s maize is irrigated, with 90% being rainfed. This is similar to other African countries.

South Africa began planting genetically engineered maize seeds in the 2001/02 season. Before its introduction, average maize yields were around 2.4 tonnes per hectare. This has now increased to an average of 5.6 tonnes per hectare as of the 2020/21 production season.

Meanwhile, the sub-Saharan African maize yields remain low, averaging below 2.0 tonnes per hectare. While yields are also influenced by improved germplasm (enabled by non-genetically modified biotechnology) and improved low and no-till production methods (facilitated through herbicide-tolerant GM technology), other benefits include labour savings and reduced insecticide use as well as enhanced weed and pest control.

With the African continent currently struggling to meet its annual food needs, using technology, genetically modified seeds, and other means should be an avenue to explore to boost production. The benefits of an increase in agricultural output are evident in Argentina, Brazil, the United States, and South Africa.

Many African governments should reevaluate their regulatory standards and embrace technology. Of course, this typically introduces debates about the ownership of seeds and how smallholder farmers could struggle to obtain seeds in some developing countries.

These are realities that policymakers in the African countries should manage in terms of reaching agreements with seed breeders and technology developers but not close off innovation. The technology developers also need to be mindful of these concerns when engaging various governments in the African countries.

Geopolitical and climate change risks present the urgency to explore the technological solutions to increase each country’s agricultural production. The Chinese regulators are following that path.

Wandile Sihlobo, Senior Fellow, Department of Agricultural Economics, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.