Getting day one right: It’s time to rethink your day one care pig protocols

Focus, don’t overdo: A data-driven approach suggests where to spend your time for the greatest impact

The hours immediately following birth can shape a piglet’s future performance and survival. That “day one” period in the farrowing house is a high-stakes environment where labor limitations, protocol implementation and biological needs all collide.

At the 2025 Four Star Pork Industry Conference held in September in Muncie, Indiana, USA, Dr. Jason Woodworth, swine nutrition research professor at Kansas State University, shared new research on drying and warming strategies, split suckling protocols and managing pig-to-teat ratios, offering a data-driven view of what matters most for piglet care in the critical first 24 hours of life.

“As you start thinking about day one care and what we're doing in the farrowing house, there's really a challenge,” Woodworth said. “In the US, there's always going to be a competition for resources. On one hand, we want to do everything we can to improve piglet health and well-being. On the other hand, we've got a labor constraint and have to work with that reality.”

The labor challenge

Labor availability in the farrowing house is one of the most significant factors shaping day one protocols. Typical staffing ratios in the United States is one employee for 350 to 400 sows. This clearly creates tight time constraints for farrowing teams. In contrast, Woodworth noted, operations in Mexico and Brazil often have one employee per 75 to 100 sows. That disparity highlights the pressure US farms face to prioritize the activities that generate the greatest benefit.

He also pointed to the frequent disconnect between on-farm realities and protocols developed at the management level.

“A lot of things we're doing for day one care are decided by people in an office behind a desk that don't spend much time on the farm,” he said. “However, if you go to the farm and talk to the people at the slat level in the farrowing house, you can better understand what they're actually doing on a daily basis and what they can realistically do on a daily basis.”

In many operations, standard operating procedures (SOPs) exist but may not be implemented as intended.

“Everybody probably has a shelf in their farm that has dusty, untouched binders like this that have their SOPs on how we're supposed to do everything during the day,” Woodworth said.

The result is a day one care environment shaped as much by human capacity and farm culture as protocols. Against this backdrop, Woodworth urged producers to focus labor where it yields the greatest benefit and let data – not tradition and habit – drive decisions.

Day one care – Start with the piglet’s environment

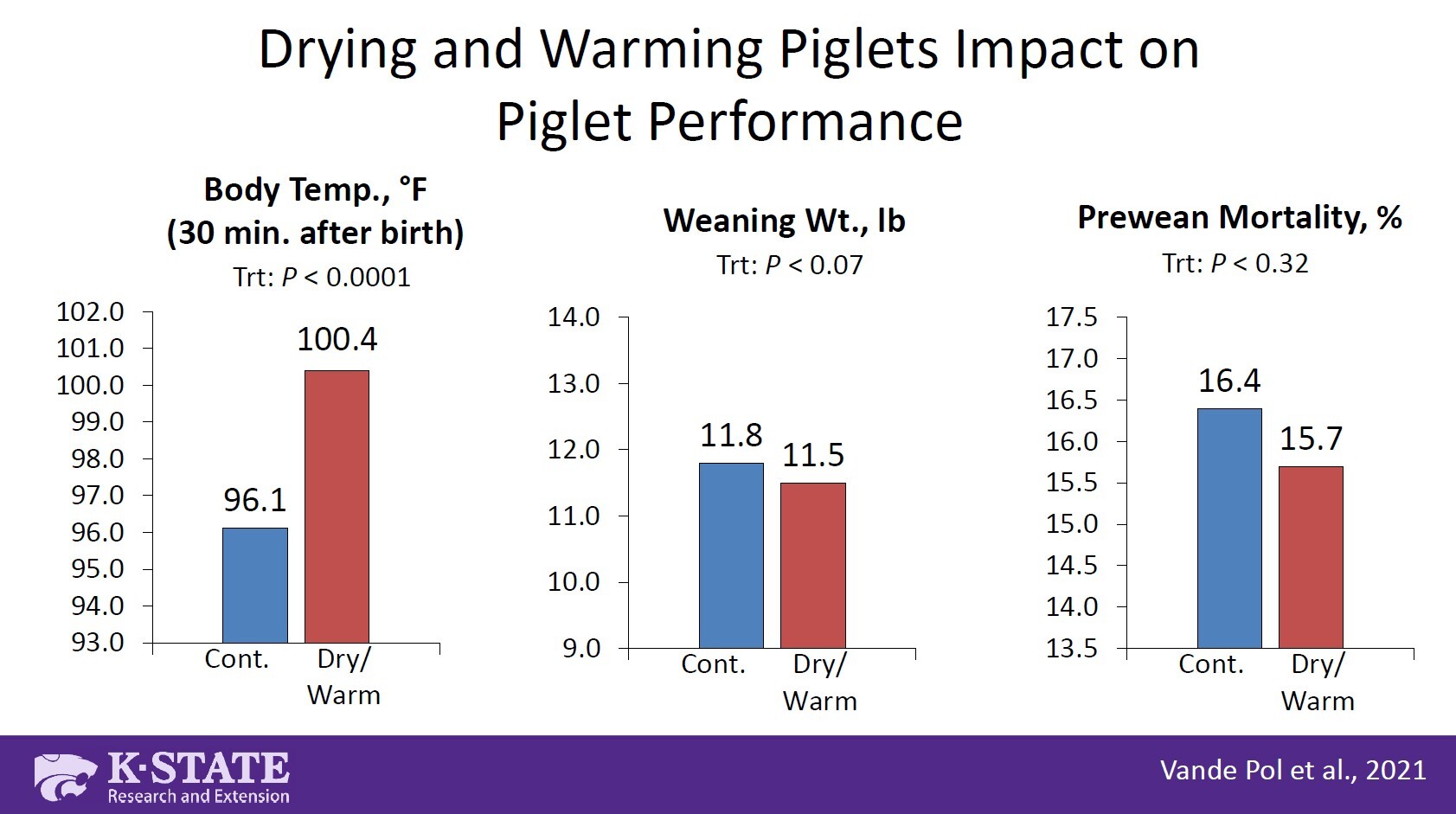

The first major focus of day one care is drying and warming piglets at birth. Piglets are born wet, with a high surface area relative to body weight. As a result, they lose heat quickly after birth, and early hypothermia is a known risk factor for pre-weaning mortality.

Woodworth says the question isn’t whether drying and warming improves piglet body temperature – it does – but how much it influences performance under different environmental conditions.

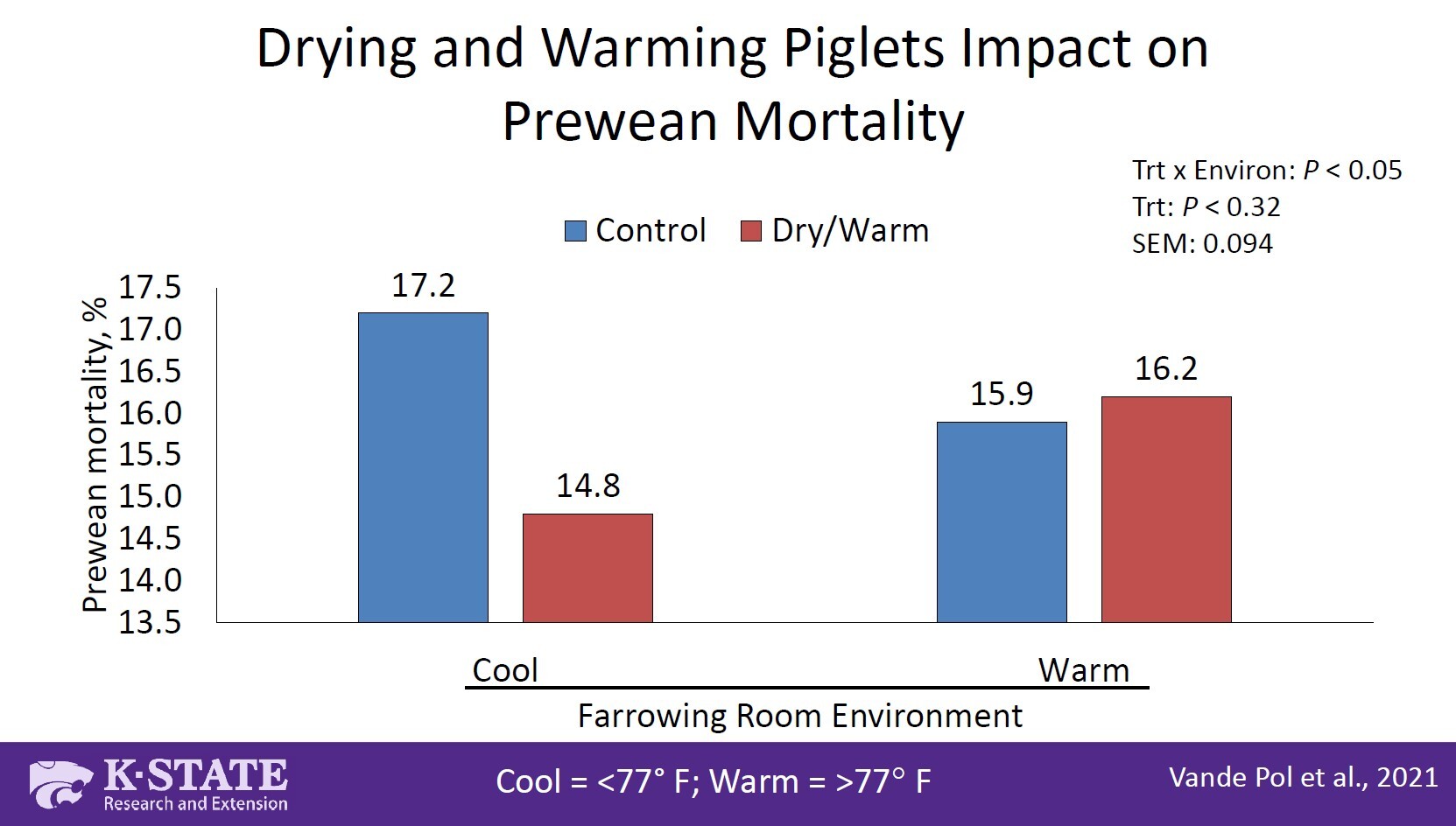

A large study conducted in collaboration with The Maschhoffs by the University of Illinois evaluated more than 800 sows and over 10,000 piglets across two farrowing room temperature environments: cooler rooms averaging below 77°F and warmer rooms above 77°F. Piglets were assigned to one of two treatments:

- Control: No drying or warming

- Drying/Warming: Application of a cellulose-based desiccant immediately after birth followed by 30 minutes in a warm box under a heat lamp

The results showed piglets that were dried and warmed maintained higher body temperatures in the first 30 minutes after birth compared to untreated piglets. In cooler rooms, pre-weaning mortality dropped from 17.2% in the control group to 14.8% with drying and warming. In warm rooms, however, no mortality difference was observed.

“The impact that we have from drying and warming these pigs is really dependent on what they're born into,” Woodworth explained. “If we're doing a good job of controlling environments in the farrowing house and make an environment that's suitable for the sow, but also suitable for that piglet, the benefits for the drying and warming is less than if we have an environment where you don't have that much control.”

Notably, drying and warming did not produce statistically significant changes in weaning weight or overall pre-weaning mortality across all environments combined. The benefit was confined to cold conditions.

For producers, the takeaway is clear: focus drying and warming efforts where they are most needed, particularly in farrowing rooms that tend to run cool. Farms that maintain optimal farrowing room temperatures may see limited return on labor invested in intensive drying protocols.

Split suckling: Is it worth the time and effort?

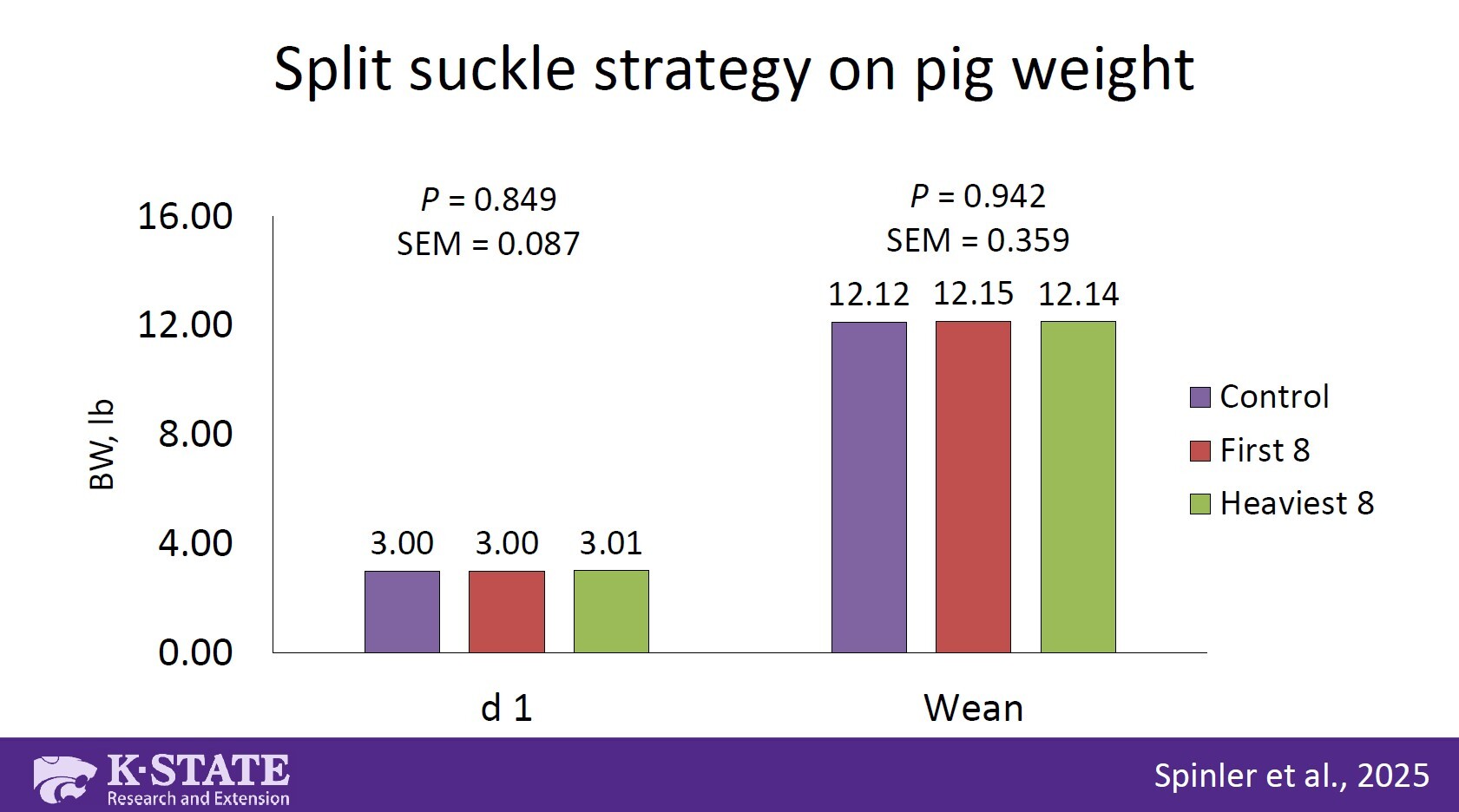

Split suckling is a widely used management practice intended to ensure smaller or later-born piglets gain access to colostrum. Although common, the data supporting its benefits have historically been inconsistent. In partnership with Pillen Family Farms, Woodworth and collaborators conducted one of the largest controlled evaluations of split suckling to date, involving more than 1,500 sows and nearly 23,000 piglets.

The trial compared three treatments:

- Control: No split suckling.

- First 8 Born: The first eight piglets were removed for 45 minutes, swapped with the later-born piglets who were removed for 45 minutes, then all pigs returned to the sow.

- Heaviest 8: The heaviest eight piglets were removed for 1.5 hours, allowing the smallest to nurse uninterrupted.

Cross-fostering occurred after treatments within 24 hours. Across treatments, researchers measured pre-weaning mortality, fallback pig removals, litter size at day one and weaning, piglet weights and post-weaning growth.

The results showed no differences in pre-weaning mortality, whether measured from day one to day two or from day two to weaning. Piglet birth and weaning weights were unaffected by treatment. Nursery and finisher performance, including average daily gain (ADG), feed intake and mortality, were also unchanged.

From 1996 to 2023, seven split suckling trials have been published. Two showed a tendency to reduce pre-weaning mortality; five showed no difference and growth results were mixed; one showed decreased growth; three showed no difference; and one showed a tendency to improve. Woodworth’s study aligns with the majority of the literature, finding little measurable benefit, especially given the amount of time and effort the practice requires.

There was one exception: among sows with more piglets than functional teats, split suckling produced a small but significant reduction in mortality from day one to day two (3.3% control vs. 2.4–2.5% for split suckling treatments). However, this benefit disappeared by weaning.

“What does this mean? At the end of the day, with the protocols that we implemented, we didn't see any meaningful difference from split suckling as far as influence in pre-weaning or post-weaning performance,” Woodworth said. “There's a lot of effort, and a lot of the people in the audience right here who likely practice this on the farm. Being able to do it right is key. And I've been into more farms that see train wrecks from trying to apply split suckling than actually getting it done right.”

For farms with tight labor, the implication is significant: split suckling may not warrant the time investment unless a sow has a litter exceeding her functional teat count—and even then, benefits are minimal and short-lived.

Pig-to-teat ratio: It’s time to rethink old rules

Modern sows are producing larger litters than ever before, but genetic progress on teat count has not kept pace. This creates a management decision point regarding nursing pressure, or the ratio of piglets to functional teats and whether to use nurse sows to handle surplus piglets, or to stock more piglets per sow than teat count would traditionally allow.

Woodworth shared data from a large study conducted with JBS in Dalhart, Texas, involving more than 1,000 sows and 15,000 piglets. Sows were assigned to one of four treatments relative to their functional teat count:

- –1: One less pig than teat count

- 0: Equal to teat count

- +1: One more pig than teat count

- +2: Two more pigs than teat count

The results showed:

- Litter size at day two increased with more piglets stocked, from 13.5 pigs in the –1 group to 16.3 pigs in the +2 group

- Litter weight at day two increased by nearly 9 lbs. across the same range.

- Mortality and removals from day two to weaning rose as well – from 11% in the –1 group to 17.1% in the +2 group – but litter size at weaning remained higher in the +2 treatment (13.5 pigs vs. 12.0 in –1).

- Average piglet weaning weight decreased modestly with higher pig-to-teat ratios, dropping about 0.7 lb. between the –1 and +2 treatments.

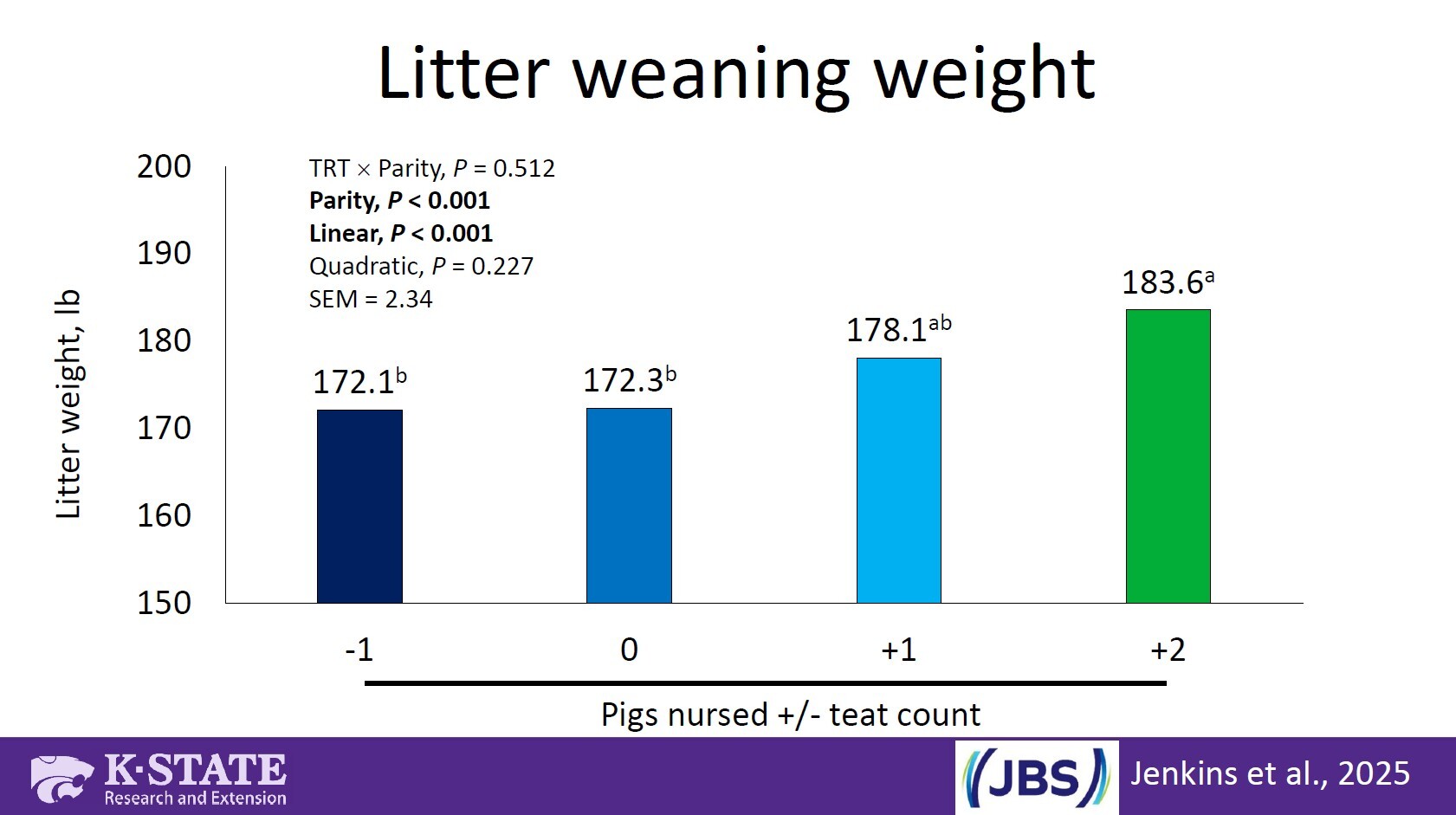

- However, litter weaning weight increased significantly, from 172.1 lbs. in –1 to 183.6 lbs. in +2.

- Moreover, pigs weaned per sow per year rose from 29.3 in –1 to 32.9 in +2.

“We used to be really careful, and the old data had said we couldn't nurse more than the number of teats that she had,” Woodworth said. “This data has really shown us that's not the case. With the litter sizes that we have, we really need to rethink this old mindset within the industry.”

These findings challenge long-held assumptions. While higher pig-to-teat ratios increase mortality risk slightly and reduce individual piglet weight, they also improve total litter output and overall farm productivity. Farms aiming to maximize pigs weaned per sow per year may benefit from stocking at +1 or +2 piglets relative to teat count, rather than relying heavily on nurse sows, according to Woodworth.

Practical priorities for day one

Woodworth suggests producers reframe day one care priorities. Rather than adding more protocols or SOPs, he urged farms to optimize environmental control, basic hygiene and sow health monitoring – factors that consistently yield measurable improvements.

“First off, it goes back to getting the environment right,” he said. “We need to make sure that the farrowing room temperature is where it should be. We need to make sure that the creep temperature is where it should be. And that's really the key. The drying and warming data supports that making sure piglets have a separate environment than the sow that satisfies their needs is going to be really important for reducing pre-weaning mortality.”

Woodworth said additional priorities include:

- Ensuring farrowing crates are clean and dry before sows enter

- Providing continuous access to clean feed and water

- Monitoring sow health individually and frequently

“If anything, this is where we can make a big difference in the farrowing house,” Woodworth said. “Let’s not forget about our sows. We want to ensure that we have daily observations on every sow, make sure that they're all getting up, they're not running a fever, they're not sick, and treat those sows in a timely manner can also have a big impact.”

Key Takeaways for Producers

Day one piglet care is about focusing on the tasks that make a difference , not more protocols. Labor is limited, and not all traditional practices deliver measurable benefits. Based on Woodworth’s research:

- Drying and warming is effective in cool environments but may not provide benefits when room temperatures are well managed.

- Split suckling shows little consistent benefit and may not justify labor investment except in cases where litter size exceeds teat count.

- Stocking more pigs than functional teats can improve total output, challenging old assumptions about nursing limits.

- Environmental control, cleanliness, feed/water availability and sow health monitoring remain the foundational tools for reducing pre-weaning mortality.

By aligning day one protocols with data and farm realities, producers can target labor and resources where they have the greatest impact – supporting piglet survival, sow performance and overall productivity.